This Policy Note is based on Chapter 1 of the book Fiscal policy in a turbulent era. Tectonic Shifts. The views expressed are purely those of the author and should not be regarded as the position of Banco de España or the Eurosystem.

Fiscal policy has regained relevance over the last two decades, a turbulent era indeed. In this SUERF Policy Note based on the conclusions of the book Fiscal policy in a turbulent era. Tectonic Shifts, by Enrique Alberola et al. analyses the multiple dimensions in which fiscal policy has returned to the center stage. The combination of low interest rates, deep economic crises and increased demands on fiscal policy are key factors for the regained importance. But the future is plagued with challenges because this period has seen a big increase in public debt and fiscal demands are also on the rise. The policy recipes to address these challenges are tackled in the last part of the note.

We are indeed living in a turbulent era for the global economy and, by extension, for fiscal policy. Just take a look at the last two decades: the global economy has gone through the two biggest recessions since the Second World War: The Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2007-08 and the Pandemic Crisis of 2020. The recovery from the pandemic reawakened inflation, dormant for decades. An anachronistic war by Russia triggered an energy crisis that entrenched inflation and clouded global economic perspectives. And the sense of economic and political despair is not fading.

The paradigm that dominated in economics since the eighties –free enterprise, markets and trade; low state intervention- has retreated in favour of something closer to Keynesianism and more intervention. One reason is that the former contributed to the imbalances and vulnerabilities that underpinned the GFC, in particular through laxity in regulation and overconfidence in the judgement of markets.

The response to the GFC, and beyond, has reshaped the role of fiscal policy and prompted a deep change in thinking. In parallel, structural, economic and social changes have shifted policy preferences that have a large imprint on public finances. The coincidence of these developments is transforming fiscal policy and challenging some of its basic principles.

The proactive role of fiscal policy and of the state in the economy is in; austerity and inhibition are out. The change has great significance. It is not clear whether we are undergoing a paradigm shift in fiscal policy or just a transitory reassessment of its role due to the changes in environment. In any case, the change is deep, lasting and consequential.

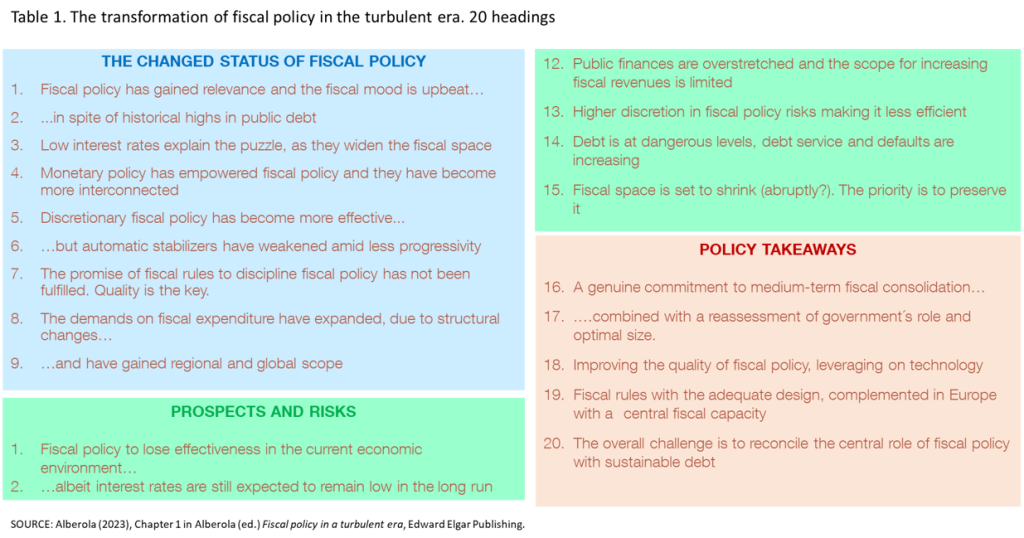

In this note, I sum up in twenty headings the profound changes -tectonic shifts we call them in the book-, that the turbulent era has brought to fiscal policy and what lies ahead. They are listed in Table 1, divided into three parts: i) the changed status of fiscal policy; ii) prospects and risks and iii) policy takeaways.

1. Fiscal policy has gained relevance across multiple dimensions and the fiscal mood is upbeat…

Fiscal policy is now more important and it has better consideration in policy and academic circles than before the GFC. The economic environment, dominated by two large recessions and very low interest rates and inflation, has demanded a strong fiscal policy response and has also enabled to make it more effective. Economic and social dynamics are expanding the demands on fiscal policy and the state at large.

The turbulent era has also consolidated a shift in economic thinking that has placed fiscal policy and the role of the state under a more benign light. Fiscal policy is now more proactive and the fiscal mood is upbeat, perhaps too much?

2. …in spite of ever higher public debt

Public debt has surged globally as a consequence of the economic crises and the required fiscal support to overcome them. A much larger supply of debt should have pushed up the financing costs and the debt service for governments. Had debt sustainability risks arisen, credit risk would have raised the sovereign yield further. The fiscal space would have shrunk, heavily constraining fiscal policy. But this has not been the case … so far: the fiscal space has been wider that could have been expected even before the increase in debt.

3. Low interest rates explain the puzzle, as they widen the fiscal space

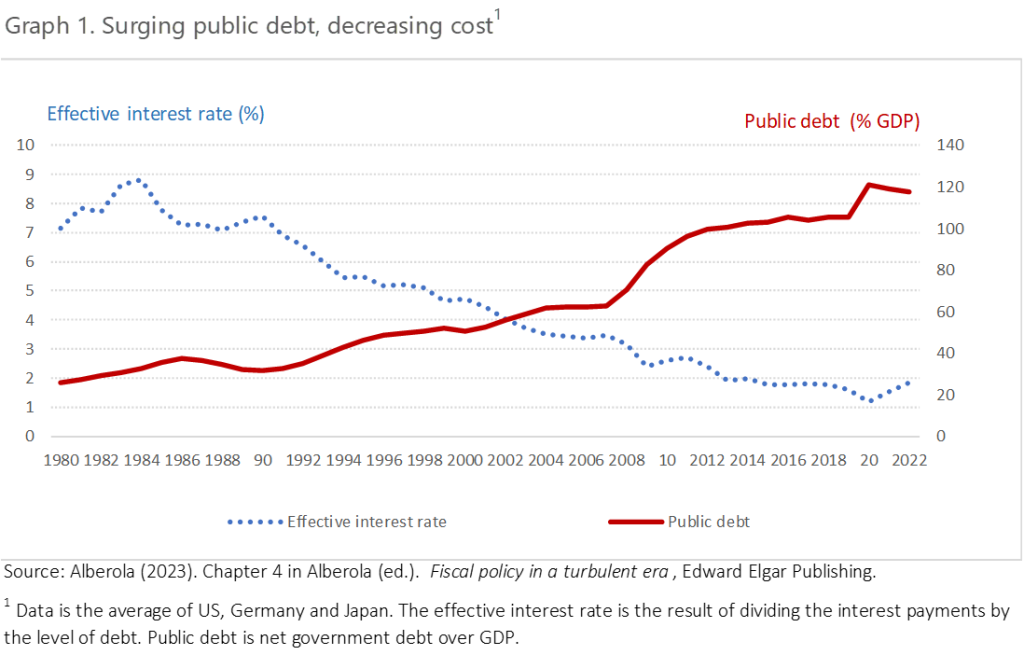

The main reason is that financing costs have been extraordinarily low. Graph 1 is indeed striking: the level and cost of debt have been negatively correlated, almost perfectly, on a long-term perspective. The reason is that the natural or equilibrium interest rate (r*) has been on a declining trend for 40 years, due to structural factors (ageing, higher inequality, low productivity growth, preference for safe assets). The reduction of the natural rate has shifted down the interest rates in the economy –including those of sovereign debt- both in nominal and real terms. The secular reduction in r* has more than offset the upward pressure that higher public debt exerts on sovereign yields. Low for long interest rates paved the way for a more active fiscal policy, as government financing remained cheap.

4. Monetary policy has empowered fiscal policy and they have become more interconnected

Inflation below target and very low natural rates in the aftermath of the GFC kept policy interest rates close to zero, even in expansions. In this context, fiscal policy was more powerful. This zero lower bound (ZLB) rendered conventional monetary policy non-operative and triggered the use of unconventional monetary policy, such as asset purchases by central banks. These tools eased financing costs at longer horizons. Fiscal expansions do not put upward pressure on policy rates at the ZLB. And monetary operations and financial regulation further in-creased the demand for public securities.

Through these multiple channels, monetary policy has supported and empowered fiscal policy in the turbulent era. In the opposite direction, fiscal policy expansions help to push inflation back to target, helping central banks to fulfill their mandate. The two-way interaction implies that the nexus between monetary and fiscal policy has strengthened.

5. Discretionary fiscal policy has become more effective…

The very low interest rates, coupled with inflation below target, also implied that central banks did not hike interest rates in economic expansions, increasing the impact of fiscal stimuli. Moreover, fiscal policy has proved to be effective in the large recessions of the last two decades. In this context, academic research has reassessed fiscal multipliers under the new environment. Multipliers are generally higher than previously thought in advanced economies (AEs); for Emerging and Developing Economies (EMDEs) there is not much evidence so far.

6. …but automatic stabilizers have weakened

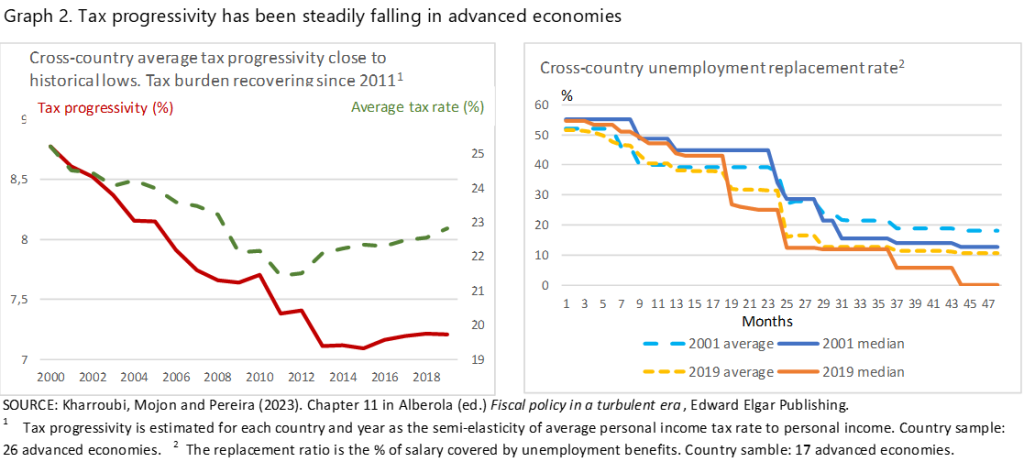

The tax structure and some types of expenditures buffer the cyclical fluctuations of the economy, providing fiscal policy with a stabilizing (countercyclical) role. Fiscal stabilizers are powerful in AEs but less strong in EMDEs, due to the belated development of the welfare state and less developed or effective tax structures. However, fiscal reforms in AEs during the turbulent era have reduced marginal tax rates on income and unemployment benefits. This decrease in fiscal progressivity (Graph 2) erodes the stabilizing role of automatic stabilizers and, by extension, of fiscal policy.

7. The promise of fiscal rules to discipline fiscal policy has not been fulfilled

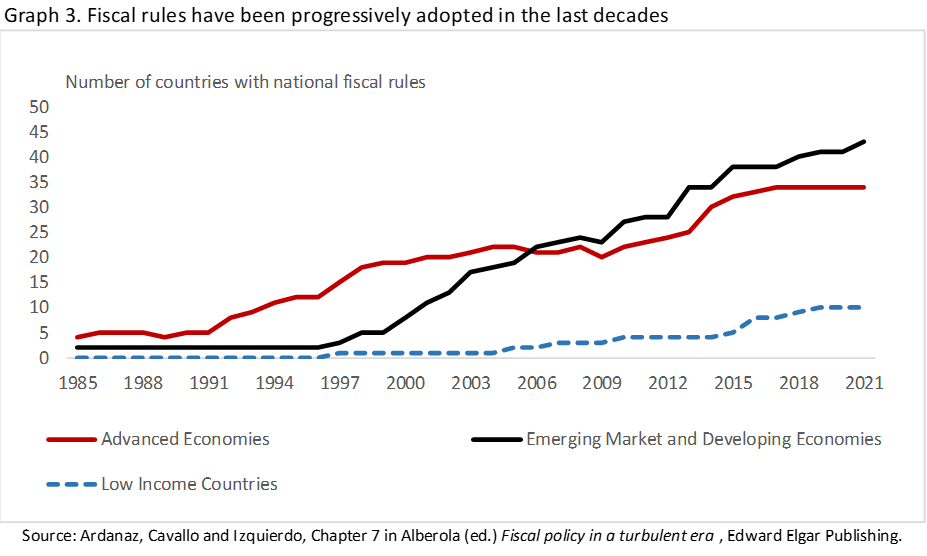

The widespread adoption of fiscal rules in the last decades (Graph 3) to rein in government’s tendency to fiscal profligacy has been only partially successful. Fiscal rules set mechanisms to constrain the budget and to discipline fiscal accounts. However, there are large differences among rules with respect to their coverage, loopholes and their degree of compliance and enforcement. These elements, summed up in the quality of the fiscal rules and of their implementation, have determined their capacity to discipline fiscal policy. Only high quality rules have limited debt accumulation, while many of them have not passed the bar in EMDEs.

8. The demands on fiscal policy have expanded…

Several factors explain the increasing demands that have burdened fiscal policy in the last decades. The most evident has been the need to respond to severe economic crisis, as noted above. Others derive from structural economic and social changes: ageing requires increasing fiscal resources through pensions, health and long-term care; increasing inequality, that fosters social discontent and polarization, is also demanding more decisive fiscal actions; the fight against climate change has a strong fiscal component, encompassing public investment, subsidies to the private sector and compensations to the losers; the role of fiscal policy and the size of the required support to the financial system was tested in the GFC. More recently, deep geopolitical shifts are demanding higher public expenditure in defense, and also in initiatives to strengthen strategic autonomy. The higher demands on fiscal policy find echo within the current fiscal mood, favorable to fiscal activism and state engagement. Some of the ideas now in vogue, like the contribution of fiscal policy to growth, would have been out of tune some years ago.

9 …and have gained regional and global scope

Global or regional challenges and issues like international leakages in corporate taxation, climate change, infra-structure networks or strategic autonomy have enhanced the relevance of international coordination and cooperation in the fiscal sphere. The agreement on international corporate taxation has been an achievement on global coordination that can inspire cooperation in other areas. The limited scope and revenue impact of the agreement underscores the difficulties of the global advances.

The European Union is a special case where the pandemic has triggered a substantial fiscal response at the central level and has put on the table the relevance of European-wide public good. This development may be –or not- the harbinger of a permanent central fiscal capacity in Europe.

10. Fiscal policy to lose effectiveness in the evolving economic environment…

The recent awakening of inflation has changed the economic landscape. Higher interest rates and tighter and more reactive monetary policy implies a reduction of fiscal multipliers, that is, of the effectiveness of fiscal policy. The surge in debt also tends to reduce fiscal multipliers as agents are more financially constrained. Finally, a return to more normal business cycles would also make fiscal policy less effective.

11. …albeit interest rates are still expected to remain low in the long run

Will this new environment herald an era of higher interest rates and inflation, where monetary policy reacts more and fiscal policy loses traction?. It is uncertain how persistent high inflation will be. Bringing the inflation genius back into the bottle can take a long time and be painful. A protracted phase of monetary tightening could keep interest rates and financing costs well above r* for a long period. A comforting factor is that r* is expected to remain low in the medium to long run, because the underlying real factors behind its fall continue to operate. This is the case of ageing and, unfortunately low growth, now extending to previously high-growth countries like China. A big question mark here is the potential impact of Artificial Intelligence developments on productivity going forward.

12. Public finances are overstretched and the scope for increasing fiscal revenues is limited

Recent fiscal activism and increasing demands on governments have overstretched fiscal policy. Spending pressures are expected to linger and funding needs will remain high, or may even increase going forward. The revenue collection capacity in AEs is close to the limit; there is little room to increasing tax rates. The reduction of the labor share in the distribution of the GDP in favor of the capital share is another challenge to increase taxation revenues, as the capital tax base is more mobile across borders. In EMDEs, the scope for broadening and improving taxation in EMDEs is generally larger, but so are the demands on expenditure, given the insufficiencies of the welfare state (pension systems, health and education).

New sources of revenue are appearing -like climate-related instruments (carbon emission rights, climate taxes). The agreement on international corporate taxation can provide a fairer allocation of taxes on profits and capital. And it can set a precedent that eases cooperation in other areas, for instance, on wealth taxes that could potentially extend the effective fiscal base. However, it is doubtful that the pace of progress is enough to finance the expanding fiscal needs.

13. Higher discretion in fiscal policy risks making it less efficient

The scope for discretionary fiscal policy has increased for good reasons, such as the need to support the economy in deep recessions, its higher perceived effectiveness and expanded demands. The weakening of automatic stabilizers also increases the relevance of discretion.

But this may erode fiscal effectiveness. Discretionary fiscal policy measures are subject to the complexities of the political process, including long implementation lags. Discretionary tools may be considered more effective now than in the past, but they are less efficient than automatic stabilizers, at least to dampen the cycle. This is how the increased importance of discretionary policy can reduce the overall efficiency of fiscal policy.

14. Debt has reached dangerous levels and debt service is bound to increase

The economic recovery after the pandemic and the spike in inflation have reduced debt ratios from the record levels of 2020. But the ratios are still much higher than pre-pandemic and further reductions will be slow.

The situation looks critical in several EMDEs, with an increasing number of countries in debt distress. The pandemic-related relief is over and sovereign defaults or stress are on the rise. The pitfalls in restructuring mechanism augur painful consequences for defaulting debtors.

A higher debt plateau combined with an increase in interest rates point to a higher cost of financing and debt service for governments in the next future. The situation may appear under control, but can change rapidly if confidence in the sustainability of debt falters and financing is cut. The increase in the number of sovereign defaults or restructurings after the pandemic is a worrying development.

15. Fiscal space is set to shrink, eventually in an abrupt manner. The priority is to preserve it

Low interest rates and favorable financing conditions opened up fiscal space in AEs. But it is contingent on the economic environment and should not be taken for granted. Higher financing costs and debt service imply less fiscal space. EMDEs know well how it can shrink in times of financial volatility. In those cases, preserving financial stability can require the commitment of large fiscal resources that may not be available. Also in the turbulent era the shocks have been bigger and the degree of volatility and uncertainty is higher than in the past.

These elements underscore the importance of preserving the fiscal space. Fiscal effectiveness and the convenient financing in the past years has been favoured by the extraordinary environment of the turbulent era and should not be taken for granted. Against this backdrop, prudence advises to rebuild ample fiscal buffers in case risks materialize.

16. A genuine commitment to medium-term fiscal consolidation…

Favorable debt dynamics driven by low interest rates is not the solution to reduce debt. Inflation, neither. Higher financial costs can quickly deteriorate debt dynamics at high debt levels. Inflation only provides a transitory respite and, if entrenched, would translate into persistent higher interest rates. The focus must be on the budget balance.

Protracted fiscal imbalances usually lead to problems. They are difficult to reverse because the political process generates a deficit bias. Even more when fiscal demands are rising, as nowadays. A sustained commitment and effort to reduce deficits with a medium-term perspective is necessary.

But the current environment is not favorable. Complacency and an ‘expansive’ fiscal mood have taken hold in recent years. The benign view on fiscal policy can be salutary but it can also be an obstacle to instill the necessary discipline. A medium-term perspective would also allow to factor in and accommodate -where possible- the expanding fiscal demands.

17. …combined with a thorough reflection on the optimal size of the government

Increasing fiscal demands conflict with the already large size of the budget and with the limits to increase fiscal revenues. New expenditures are accommodated generally in an ad hoc manner. Not much thoughts or resources are devoted to assess whether the increased expenditures can be sustained through time, also considering the committed future expenses related to ageing. Kicking the can down the road is not a permanent option. At some point choices will have to be made.

18. Improving the quality of fiscal policy, leveraging on technology

Improving fiscal management and the quality of fiscal policy would help to mitigate the fiscal constraints and risks. The more prominent role of discretionary policy calls for making the process more efficient. Admittedly, the policy reaction to the pandemic was swift and quick. Lessons can be drawn from this positive experience, also for non-emergency situations.

In EMDEs, the gaps to fill are much bigger. There, the fiscal reforms have to be aimed at broadening the fiscal base, as well as improving efficiency. More fiscal resources would facilitate the funding of better public services, fundamental for a more inclusive and sustainable growth.

The challenge in AEs economies is to anchor the fiscal base, avoiding domestic and international leakages. The move towards taxing (global) property and wealth is gaining traction. With the international agreement on taxation, this move could overcome some of the current constraints for effective and fairer taxation.

Fiscal policy can also exploit the opportunities of digitalization. For instance, digital transfers based on data helped to provide fiscal support in EMDEs to those needed during the pandemic and to surface informal activities. Proper use of digital finance could help in this way to target policies much finely, contributing to a better approach to mitigate inequality and saving resources. Digital tracking, and the increasing use of Artificial Intelligence, combined with the international information exchange initiatives developed after the GFC can also help to reduce tax avoidance.

19. Fiscal rules with the adequate design, complemented in Europe with a central fiscal capacity

Fiscal rules can be useful to discipline fiscal policy, if properly designed. The design, management and implementation of fiscal rules is a learning process. The experience of first generation rules was generally disappointing but lessons are being incorporated in reshuffled designs. New rules often include provisions for unexpected shocks, are framed in a medium-term perspective, are contingent on debt thresholds and convey enforcement mechanisms. The reformed rules have more chances to serve their original purpose, but the strength of the underlying institutions continues to be key.

The reform of the fiscal rules in the EU follow some of these guidelines, but it says nothing on the establishment of a permanent central fiscal capacity. The case for a central fiscal capacity in the EU was originally related to the stabilizing role of fiscal policy at the regional level. It gathered wide support among analysts and academics before the pandemic, but clashed with political resistance. The rise of economic challenges that can be only properly tackled at the regional or global level (climate change, infrastructure for strategic autonomy and digitalization, etc) has reinforced the need and urgency of a centralized fiscal mechanism with sufficient muscle. At least there is an increasing awareness of the existence of European-wide public goods that may encourage steps in that direction.

20. The overall challenge is to reconcile the central role of fiscal policy with sustainable debt

All in all, the turbulent era has been a good time for fiscal policy. In spite of higher debt, financial conditions widened the fiscal space and it was duly used. Stakeholders favored a proactive fiscal policy. The demands and expectations on fiscal policy have increased and probably will not recede. But the economic backdrop is changing.

Going forward, an active and effective fiscal policy requires to maintain the fiscal space amid growing pressures. The biggest risk is that markets doubt at some point that debt is sustainable. That would squash the fiscal space when it is most necessary. A fiscal policy that promotes medium-term consolidation is central to reduce debt and safeguard the fiscal space. The consolidation should be framed in a deep and thorough reflection on the size and limits of public policies.

Will policymakers deliver? The fiscal mood for activism remains and fiscal discipline is elusive when there are no strong market or institutional pressures. A disorderly adjustment amid financial stress would be dangerous and that prospect should be enough to act responsibly. The signs of fiscal restraint are scant so far, but time will tell.