The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Central Bank or the Bank for International Settlements.

The link between wages and prices, the so-called wage-price pass-through, is a key ingredient to understand inflation developments. In this column, we examine the pass-through from wages to producer prices using sectoral disaggregated data for the euro area. We document a significant wage-price pass-through, which however differs markedly across sectors. The pass-through in private services is significantly higher than in industry and takes longer before reaching its peak. While a higher labour intensity is a key reason for a higher pass-through in services, our estimates indicate that differences in sectoral labour shares alone cannot explain the differences compared to industry. Instead, estimates hint at an important role for international competition in the domestic market for the tradeable sector.

With the resurgence of inflation in 2021, wage developments also came to the fore. Surprise inflation first eroded real purchasing power and then prompted central banks and observers to ask whether potential wage increases could affect the persistence of inflation and make the “last mile” of the ongoing disinflation more challenging (Schnabel, 2023). In some ways, this mirrors discussions in the years prior to the pandemic, when central banks had to deal with sluggish price growth in the context of strong labour markets, and illustrates how the link between wages and prices, the so-called wage-price pass-through, is a key element in understanding inflation developments.

In a recent paper (Ampudia et al., 2024), we examine the pass-through from wages to producer prices in the euro area using sectoral disaggregated data and study whether it differs across sectors. We then investigate the causes of a different wage-price pass-through between industry and services.

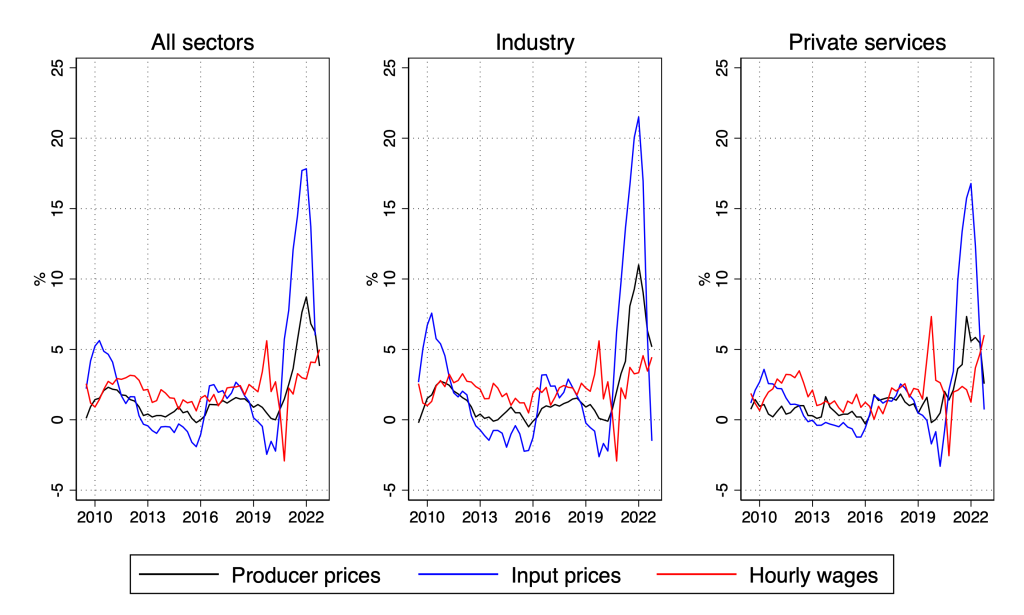

Figure 1 shows the median growth in sectoral wages and prices in the euro area since 2009, and separately for industrial and private services sectors.1 Between 2009 and 2019, the changes in producer prices and in input prices were on average below 1% across sectors, both in industry and private services. The post-Covid period was marked by a sharp increase in prices. In particular, input prices increased rapidly and relatively more in the industrial sector than in private services, due to energy and supply chain disruptions. By contrast, wages in private services grew at a faster pace than in industry lately.

Figure 1. Sectoral wage and price dynamics in the euro area

Sources: Eurostat and authors’ calculations.

Notes: The figure represents the median growth increases in producer prices, input prices and wage per hour worked in euro area sectors.

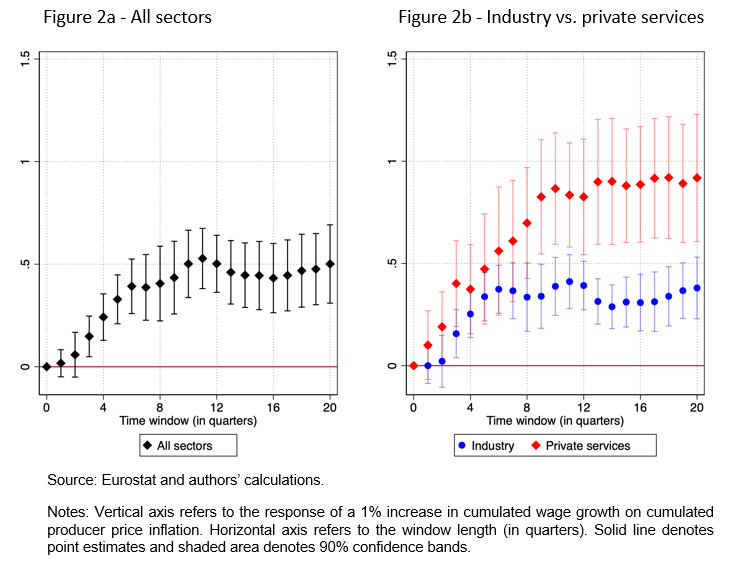

To study the response of producer prices to changes in wages over time, we estimate a wage-price pass-through equation over different time windows. We first investigate the average response for all sectors and then separately for the industrial sector and for private services.2

Figure 2a represents graphically the results, pointing at a significant wage-price pass-through over the different time horizons. The pass-through gradually increases to around 40% over an 8-quarter period. This implies that a 10% cumulated increase in wage growth over two years is associated with a cumulated increase of 4.1% in producer prices. The effect then peaks at 50% after three years and stabilises at this level for longer time windows. These estimates are quantitatively larger than the pass-through estimates for the United States based on similar disaggregated sectoral data.3

However, Figure 2b hints at very different dynamics between industry and private services. In the short run, the wage pass-through builds up gradually in both sectors. Over a one-year horizon, it reaches 25% in industry and 38% in private services, even though these estimates are not statistically different between each other. The dynamics then start diverging thereafter. After one year and a half, the pass-through of wages to prices in industrial sectors stabilises between 35% and 40%, and remains at this level over longer time windows. By contrast, it takes one additional year for wage growth in services sectors to fully deploy its effects on prices: the pass-through is estimated to be nearly full (86%) over a horizon of two years and a half. At this horizon, the estimated pass-through in services is twice as large and significantly different (statistically) to that in the industrial sector.

Figure 2. The wage-price pass-through is significant in the euro area and is stronger in private services than in industry

Differences in the pass-through across sectors are likely underpinned by structural factors: some relate to differences in the production process (most importantly, the share of labour input), while others to the different degree of competition across sectors.

Our results first suggest that, while labour-intensive sectors pass on relatively more increases in wage costs, differences in sectoral labour shares alone cannot explain the larger wage pass- through in private services compared to industry.

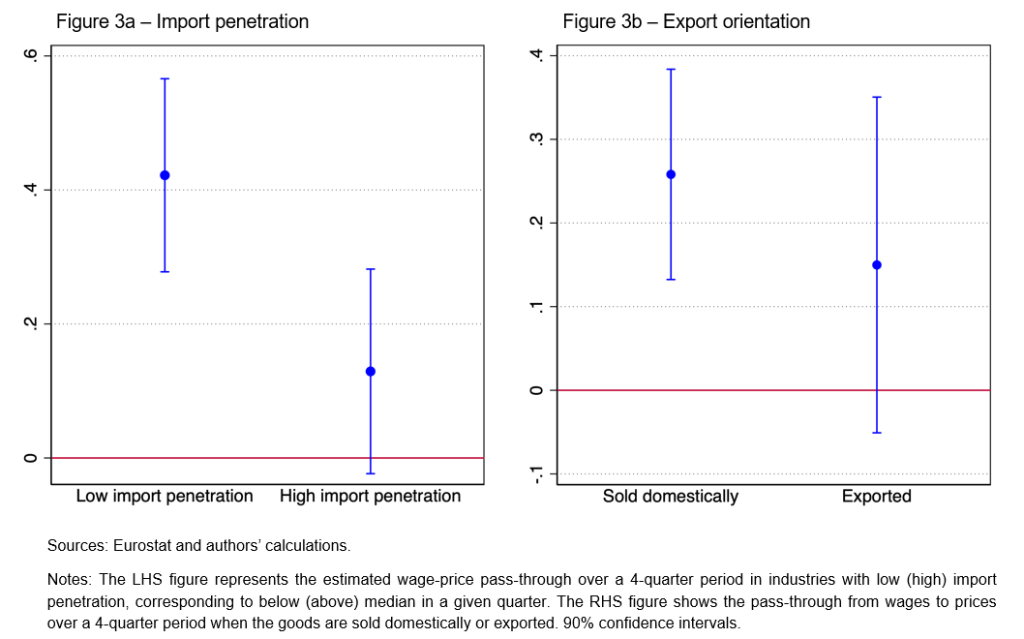

A key difference between industry and services relates instead to the degree of international competition, as industrial sectors are more exposed to globalisation, while private services tend to be more domestically oriented.4 Our estimates suggest that a greater import penetration lowers the wage pass-through in industrial sectors (Figure 3a). In the sectors least exposed to import competition, the wage pass-through is positive and statistically significant, estimated at 43%. By contrast, when the degree of import competition is high, the wage pass-through amounts to only 16% and is not statistically significant.

Yet another aspect of intense international competition is that it could also impair the ability of industrial firms to pass on rising domestic costs to their export prices. To explore this channel, we look at PPI indices by sales destination for industrial sectors, and find that the pass-through from wages to prices is significant when the goods are sold domestically but insignificant when the goods are exported (Figure 3b). Therefore, wage growth contributes to domestic goods inflation but not to export inflation, at least in the short run.

Figure 3. The wage-price pass-through is lower in the industries exposed to globalisation

Our results point to a substantially higher pass-through in the services sector compare to industrial sectors. This partly reflects a higher labour intensity, but also a more limited degree of competition. In this respect, we also found that industrial sectors that are less exposed to the competition of foreign firms, both in the domestic market and internationally, have a higher degree of pass-through.

Our results underscore the importance of considering sectoral heterogeneity when formulating a monetary policy response to wage pressures. More specifically, wages catching up to recover the purchasing power lost because of surprise inflation will likely lead to comparatively larger price pressures in services. In turn, this is likely to make services inflation stickier.

Amiti, M., Heise, S., Karahan, F., and Sahin, A. (2023). Inflation Strikes Back: The Role of Import Competition and the Labor Market. NBER Working Papers 31211, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Auer, R. and Fischer, A. M. (2010). The effect of low-wage import competition on U.S. inflationary pressure. Journal of Monetary Economics, 57(4):491–503.

Bobeica, E., Ciccarelli, M., and Vansteenkiste, I. (2019). The link between labor cost and price inflation in the euro area. Working Paper Series 2235, European Central Bank.

Heise, S., Karahan, F., and Sahin, A. (2022). The Missing Inflation Puzzle: The Role of the Wage-Price Pass-Through. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 54(S1):7–51.

Ampudia, M., Lombardi, M., and Renault, T. (2024). The wage-price pass-through across sectors: evidence from the euro area. Working Paper Series No 2948, European Central Bank. Working Paper Series No 1192, Bank of International Settlements.

Schnabel, I. (2023). The last mile, Keynote speech at the annual Homer Jones Memorial Lecture, St. Louis.

Sectors are at the 2-digit level and are defined according to the Eurostat NACE Rev. 2 nomenclature.

As such, our approach relates to the recent work of Heise et al. (2022) and Amiti et al. (2023). Specifically, we regress the cumulative change in producer prices over the cumulated change in hourly wages for different time windows, controlling for the corresponding change in input prices, labour productivity and economic activity.

Heise et al. (2022) find for instance a pass-through of 12% over an 8-quarter period. Our estimates are consistent with previous macro-level evidence for the euro area, e.g. Bobeica et al. (2019).

Earlier evidence for the United States shows that import competition exerts downward price pressures in manufacturing industries, which contributes to the lower wage-price pass-through (Amiti et al., 2023; Auer and Fischer, 2010; Heise et al., 2022).