Is central bank money “magic money” that could be used to avoid issuing government debt or extinguish existing debt? This policy brief explains what is central bank money, how it is created, and the relationship between central bank and government finances. There are no easy options to avoid paying for fiscal deficits.

Although central banks have a special role, they are still banks. They issue financial liabilities and hold financial assets. They are generally owned by their governments and their net profits are regularly transferred to the Treasury through dividends. The consolidated balance sheet of euro area central banks is published every week by the European Central Bank (ECB).

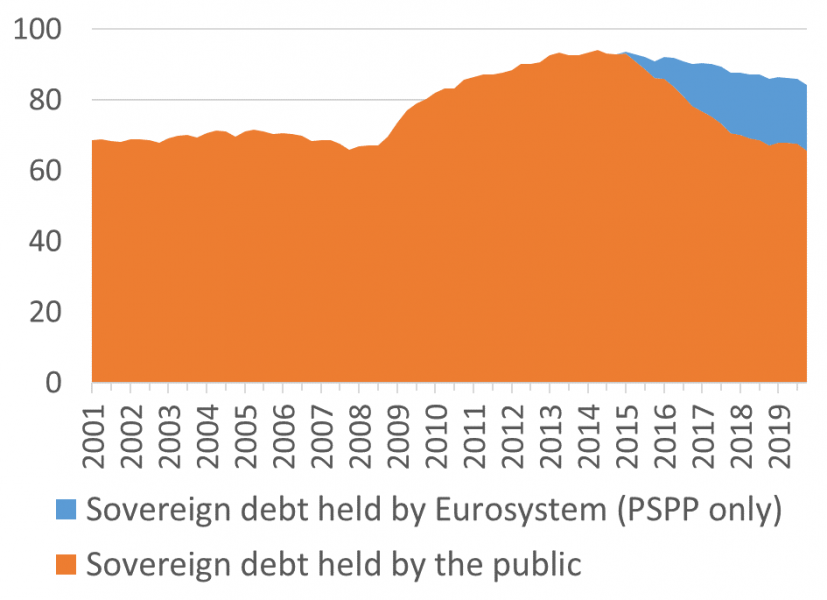

Chart 1: Sovereign debt held by the Eurosystem as a % of GDP

Source: ECB; Note: last data point Q4 2019. Public sector purchase programme (PSPP)

Central banks issue two important types of liabilities, which comprise the monetary base: banknotes in circulation and deposit and current accounts.

Banknotes – the euro bills in your wallet – are printed by central banks. They are sold to retail banks on demand in exchange for interest-bearing claims so that your bank can give them to you when you make a cash withdrawal.

Banknotes do not earn interest. Since banknotes cost very little to print but are exchanged at face value, central banks earn seigniorage revenue on the issuance of banknotes because the financial claim yields a return that, in general, exceeds the zero return on money. There are currently about EUR 1.2 trillion worth of euro banknotes in circulation throughout the world. The value of a banknote comes from its role as legal tender and the public’s confidence in the fact that its purchasing power will not be eroded by inflation.

Central bank accounts are provided to domestic banks, international financial institutions and governments to facilitate payment flows between them. When you pay for a laptop using a credit card, then the transfer from your bank account to the seller’s bank account ultimately involves a transfer from your bank to their bank across their respective accounts at the central bank. Major central banks pay interest on these deposit accounts or current accounts, and it is via these rates that central banks steer other interest rates in the economy and thereby implement monetary policy. The deposit facility rate of the ECB is currently negative, at -0.5%, which implies that banks are paying to hold their reserves at the central bank.

On the asset side, central banks hold gold and foreign exchange reserves, collateralised loans to banks and outright purchases of euro area government and corporate bonds (and a few other things). Historically, the ECB and the national central banks – the “Eurosystem” – used collateralised loans to banks (known as repos) to regulate the amount of reserves in the system and influence the interest rate on borrowing between banks. Since 2015, the Eurosystem has purchased around EUR 2.8 trillion worth of bonds under its Asset Purchase Programme (APP) as an additional tool of monetary policy (see Figure Chart 1). On 12 March 2020, this was extended by a further EUR 120 billion, and under the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) announced on 18 March 2020 the Eurosystem will purchase an additional EUR 750 billion worth of assets by end-2020.

The assets purchased by the Eurosystem include government bonds, corporate bonds, asset-backed securities and covered bonds. Purchases are allocated across the national central banks and the ECB, and government bonds are bought more or less in proportion to the fraction of the capital of the ECB held by each member. So French government bonds comprise about 20% of government bond purchases under the APP and these are mostly purchased by the Banque de France (BdF). The breakdown of purchases across countries is more flexible under the PEPP.

When the Banque de France purchases a French government bond from a French bank, it credits the deposit account of that bank at the BdF. The Banque de France now earns interest income from this bond and pays interest on the deposit created – both interest rates can be negative. As long as the yield to maturity (rate of return on the bond) is above the deposit rate, the Bank earns a profit, which it eventually transfers to the French Treasury.

Since the central bank owns government debt and the government owns the central bank, cannot government debt held by the central bank be cancelled leaving the combined balance sheet unchanged? No, not only is annulling sovereign debt illegal in the euro area, but the central bank also still owes interest on the deposits created. This is not a problem now since the deposit rate is negative, but may become a problem when the deposit rate becomes positive. The central bank will owe money without any income to pay for it. The central bank will also record a significant capital loss.

There are mainly two possibilities to resolve this income deficit: either the transfers between the central bank and the government serve to absorb the loss, or the central bank repays by issuing new reserves. In the first case, the government has to accept a lower monetary dividend. In the second, whilst it is true that central banks can always create additional deposits to pay for this shortfall, this risks becoming a pyramid scheme, as the central bank has to issue increasing volumes of deposits to pay interest on its existing reserves. Banks will have more and more central deposits, for which there is little prospect of obtaining real value. Unilaterally issuing additional deposits is also not an option for individual central banks of the Euro-system. Inflation is the inevitable consequence when households and firms begin to have doubts about the value of this money and begin to spend their money before its purchasing value disappears. This may trigger an inflationary spiral.

A similar problem would occur with monetary finance – paying for public expenditure through central bank money creation. A central bank can simply credit funds to the government’s account. But when this money is spent, the deposits will be transferred from the government’s account to a bank’s account (similar to the laptop example). The central bank will owe interest on this deposit but without any additional asset to pay for it. A similar inflationary spiral can begin.

Over recent years, inflation has consistently undershot the ECB’s target of below, but close to, 2% and inflation expectations are generally low. The risk of an immediate outbreak of inflation seems unlikely. However, a central bank that loses control of its balance sheet and cannot be recapitalized, permanently loses its capacity to control any future inflation. It is this permanent loss of control that poses the greatest danger and could de-anchor inflation expectations. The level of inflation that would result from a loss of confidence in money is uncertain and may well be much more than the central bank’s mandate.

It is also true that central banks can and do continue to function with negative equity but this is only possible if it is limited and does not continue to grow exponentially. This requires the government to make transfers back to the central bank if the payments owed on the central bank’s liabilities exceed the revenues from its assets. A central bank can only operate with negative equity if the net payment flows between the central bank and the government are equivalent to a positively capitalized central bank with the same liabilities. In other words, annulling debt would have no impact on the solvability of the state for an unchanged path of current and future inflation. Moreover, control over inflation would now depend on transfers from the government and the central bank would no longer be fully independent in setting monetary policy.

The demand for safe assets, like central bank reserves, has also increased, particularly since the financial crisis. As a result, interest rates are likely to remain low, minimizing the risk of an inflationary spiral. But if this is the case, rolling over public debt can also be done at low interest rates and lead to similar results without any role for debt cancellation; and hence should be preferred to preserve central bank independence and ability to fulfil its mandate. There is thus nothing magic about central bank money.