We study if ultra-easy monetary policies have led to the zombification of firms and lower growth and financial vulnerabilities in the United States (U.S.), Eurozone countries, and Japan. We find that expansionary monetary policy can help reduce zombification when interest rates are at the zero lower bound (ZBL), but an ultra-easy monetary policy for extended periods is associated with a higher probability of zombification. This raises concerns about the sustainability of too-easy monetary policy implementation, especially in countries where growth is lackluster. Our findings imply a tradeoff between conducting a countercyclical monetary policy and using an expansionary monetary policy for long periods, which may lead to a combination of low interest rates, low growth, and high financial vulnerability. Such a tradeoff is not a concern currently when most countries are tightening their monetary policy stance, but policymakers should be mindful of it during future recessions.

Extended periods of ultra-easy monetary policy in advanced economies have rekindled debates about the zombification of weak companies and its impact on resource allocation, economic growth, inflation, and financial stability. Critics argue that when interest rates remain low for extended periods, financially weak companies, which otherwise would fail, can survive due to cheap credit. This leads to a “zombification” of weak firms that are kept alive by continued borrowing. While this prevents immediate job losses, it also ties up resources that could be utilized more effectively elsewhere, leading to misallocation. These zombie firms, unable to innovate, tend to be less productive and can even adversely affect the operations of healthier competitors, ultimately leading to lower growth and financial stability issues. This paper summarizes the findings of Jafarov and Minnella (2023) on this subject.

We use firm-level annual data for publicly traded companies and small firms from the Orbis database, provided by Bureau Van Dijk, with around half a million firm-year observations. The dataset spans 1996 to 2021 and contains balance sheet data and ratios for around 60,000 companies. According to our definition, a firm is classified as a zombie if it is at least ten years old and its interest coverage ratio (ICR), defined as the ratio between earnings before interest and taxes and interest payments, is lower than one for at least two consecutive years. The first requirement allows not to include as zombies some relatively young, healthy corporates which might suffer initial losses due to their high investments – some of which through high loan volumes – in their first years of activity. In addition, we allow firms to fluctuate between the zombie and non-zombie states whenever the conditions above are not met. By doing so, we can detect the year-specific characteristics of a firm and link them to the current monetary policy implementations to inspect their correlation in the recession and ZLB periods. To check the robustness of our results, we also repeat the analyses using an alternative definition of zombie firms, under which a company’s ICR is below one in three successive years, which produces similar results. Macro data come from the authorities of the respective countries as well as the International Monetary Fund.

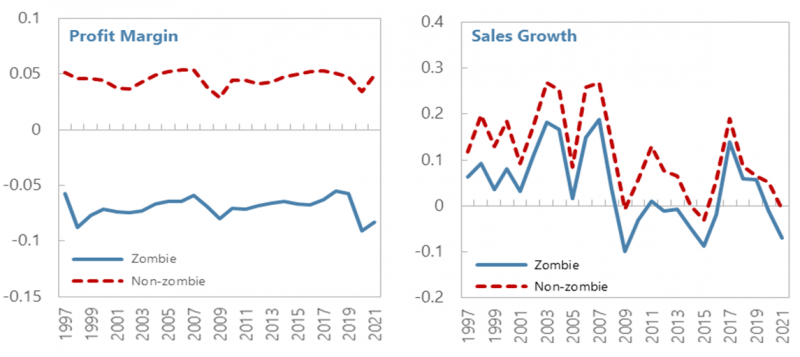

Almost by definition, zombie firms are more indebted, and most make losses. They also recorded lower sales and employment growth (Figure 1). But most of them were still increasing their sales, employment, and borrowing except for the aftermath of the global financial crisis, suggesting that they might have taken market shares from their healthier competitors.

Figure 1: Zombie vs Non-zombie Performance

Sources: Orbis database, and the authors’ estimates.

We use OLS and probit models to study the factors of zombification. We find that recessions are a critical factor in the rapid increase in the number of zombie firms. The probability of becoming a zombie company is higher for small or medium-sized companies, perhaps reflecting the fact these companies are less subject to global competition. As expected, higher GDP growth or return on assets are associated with a lower probability of being a zombie.

The impact of monetary policy, represented here by the shadow rate (taken from Krippner. 2013), on zombification depends on the economic cycle in which decisions are made. When interest rates are at or near zero, expansionary monetary policy (low interest rate) can reduce the likelihood of zombification. However, in other periods, these same policies actually increase the likelihood of zombification.

While ultra-easy monetary policy at ZLB can help reduce the probability of zombification, extending such policy to longer time horizons can increase the probability of zombification. We study this by introducing a dummy variable capturing periods when the short-term policy rate was kept low for an extended period. We set it equal to one if two conditions apply: first, if the policy rate was lower than 25 bps for at least two consecutive years, and second, if quantitative easing (QE) was not implemented. This second requirement ensures that we can capture the implementation of persistently low-interest rate policies without mistakenly including the effects of QE on firms’ borrowing costs and other financial indicators.

We find that long periods of low interest rates are correlated with higher probabilities of having zombie firms. As discussed by Caballero and others (2008), when interest rates are very low and banks are subject to strict capital requirements, their willingness to keep lending to unprofitable firms can generally increase as they may hope for government support to the borrowers. Furthermore, the longer interest rates are kept low, the more likely the agents will believe that the central bank will stick to a low-interest rate policy, even exacerbating this mechanism. This is mainly captured by the Japanese experience, which was the first country to adopt the ultra-easy monetary policy with the implementation of the ZIRP before extensively using QE for the first time in an advanced economy.

The previous analyses suggest that a too-accommodative monetary policy in extended periods can facilitate zombification, but it needs to be clarified if the rise of zombie firms would reduce economic growth. On the one hand, at the firm level, we found a negative correlation between GDP growth and the probability of being a zombie firm. On the other hand, this relationship is only sometimes significant on the macroeconomic side. To shed light on this matter, we estimate a Bayesian panel VAR on the three geographical units of our sample corresponding to monetary unions, namely the United States, Japan, and the Eurozone. We identify the structural shocks using a Cholesky ordering. The variables of the system are the region-specific zombie share, the CPI inflation rate, the output gap, and the shadow rate in that order, based on the idea that monetary policy shocks do not have contemporaneous effects on the other variables of the system, which is consistent with the existing literature on SVAR models, including Bernanke & Mihov (1998), Christiano and others (1999) and Primiceri (2005). It is worth noting that the results are robust to different Cholesky ordering.

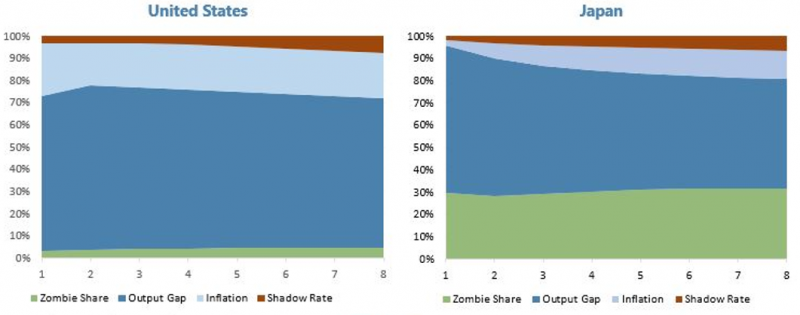

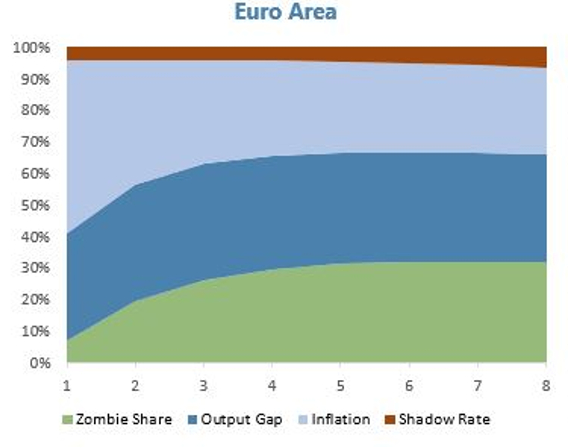

The results suggest that the increase in zombie firms correlates negatively with GDP growth. Moreover, Japan and the Eurozone appear to have suffered the most from the rise of zombie firms (Figure 2). Specifically, each chart in Figure 2 corresponds to the region-specific forecast error variance decomposition of the output gap resulting from the panel VAR estimation. The output gap explains most of its variance throughout the response horizon period in all three regions. However, while the zombie share explains around 6 percent of the variability of the output gap in the US, this contribution accounts for up to 30 percent in Japan and the Eurozone. This finding suggests that Japan and the Eurozone experienced the sharpest economic slowdown explained by the zombification of its corporate sector.

Figure 2: Forecast Error Variance Decomposition of the Output Gap

Notes: Each chart shows the region-specific percentage of the variance of the output gap, respectively explained by shocks in the zombie share in green color, the output gap itself in blue, and the shadow rate in red.

Sources: Orbis database, IMF WEO database, and the authors’ estimates.

Furthermore, we find that an increase in the sector-specific zombie share exerts a sizable reduction on both the employment growth and the profit margin of non-zombie firms operating in the same sector. Our results are consistent with Banerjee and Hoffman (2018). What might be in place is a potential transmission channel that leads to a more general resource misallocation problem. If prolonged periods of an ultra-easy monetary policy increase the probability that unprofitable firms keep on “floating,” the market will indirectly deprive the healthier firms of investment possibilities, in turn leading to lower employment and profits. In this sense, very low level of interest rates over extended periods could be considered a form of financial repression.

The existing literature highlights the role of a weak banking sector in the emergence and survival of zombie firms. Undercapitalized banks often “evergreen” loans to weak companies to avoid additional provisioning that could diminish their reported capital adequacy ratios. Several analysts argue that this phenomenon was observed in Japan in the 90s and in Europe after the global financial crisis (see Caballero and others (2008) and Blattner and others (2019).

We try to measure banks’ leniency towards weaker companies in the U.S. by assessing trends in the Senior Loan Officer Surveys on Bank Lending Practices (SLOSOBL). There is a correlation between reduced shadow rates and loan standards, which suggests leniency towards weaker companies. However, Favara and others (2021) find that U.S. banks do not seem to offer credit at favorable terms to zombie firms. They, on average, charge zombie firms higher loan spreads, require more collateral, and offer shorter-maturity loans than non-zombie firms. Moreover, banks appear to assess zombie firms as having a higher probability of default and systematically rate their credit ratings lower than the other firms.

Overall, related financial sector risks in the twenty-one countries studied appear manageable in the short-to-medium term. Banks have significantly improved their lending and loan classification practices, capital and liquidity adequacy ratios, and stress testing capacity in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, especially in the context of Basel III reforms. Recent stress tests by banks, respective authorities, and the IMF (in the context of the respective Financial Sector Assessment Programs, FSAP) suggest that the financial systems in these countries can weather large but plausible shocks. Moreover, the countries have significantly improved their financial sector supervision and crisis management and resolution frameworks, notably with respect to early warning systems and pre-insolvency frameworks, which means that they can identify adverse trends and manage crises if they occur. Yet, declining profitability ratios of financial institutions, increasing risk-taking behavior, and recent bank failures in the U.S. and Europe suggest that risks need to be closely monitored.

While expansionary policies may boost economic activity and financial indicators of both zombie and non-zombie firms and are needed to smoothen economic cycles, extended periods of ultra-easy monetary policy may have undesirable adverse effects. We find that using ultra-easy monetary policy for extended periods facilitates the survival of zombie firms, adversely affecting non-zombie firms through resource misallocation and reduced market shares, thus hurting economic growth. The adverse effects of ultra-easy monetary policy on zombification are more visible in Japan and the Eurozone. In particular, the adverse effect of the increased zombification on the output gap is the highest in Japan and the EA. These raise concerns about the sustainability of too-easy monetary policy implementation, especially in countries where growth is lackluster.

These findings imply a tradeoff between conducting a countercyclical monetary policy and using an expansionary monetary policy for long periods, which may lead to a combination of low interest rates, low growth, and higher financial vulnerability. Such a tradeoff is not a concern currently when most countries are tightening their monetary policy stance, but policymakers should be mindful of it during future recessions.

The adverse effects of ultra-easy monetary policies can be largely reduced if the banking system is healthy and well-supervised and differentiates between strong and weak firms in such a way that encourages healthy competition. In this context, the important reforms since the global financial crisis have rendered the financial systems stronger and more robust to shocks. Accordingly, the risks of evergreening non-performing loans have significantly declined. Yet, there remain risks to financial stability from the ultra-easy monetary policy for extended periods, especially if these may need to be followed by policy tightening in later periods, which need to be closely monitored.

Banerjee, R. & Hofmann, B. (2018), “The Rise of Zombie Firms: Causes and Consequences,” BIS Quarterly Review, September.

Bernanke, B. S., & Mihov, I. (1998), “Measuring Monetary Policy,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 113(3), 869-902.

Blattner, L., Farinha, L., & Rebelo, F., (2019), “When Losses Turn into Loans: the Cost of Undercapitalized Banks,” Working Paper Series 2228, European Central Bank.

Caballero, R. J., Hoshi, T. & Kashyap, A. K. (2008), “Zombie Lending and Depressed Restructuring in Japan,” American Economic Review 98(5), 1943–77.

Christiano, L. J., Eichenbaum, M., & Evans, C. L. (1999), “Monetary Policy Shocks: What Have We Learned and to What End?” Handbook of Macroeconomics, 1, 65-148.

Favara, G.,, Minoiu, C.,, and Perez-Orive, A. (2021). “U.S. Zombie Firms: How Many and How Consequential?,” FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, July 30, 2021, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.2954.

Jafarov, E., Minnella, E. (2023). “Too Low for Too Long: Could Extended Periods of Ultra Easy Monetary Policy Have Harmful Effects?” International Monetary Fund Working Paper WP/23/105.

Krippner, L. (2013), “Measuring the Stance of Monetary Policy in Zero Lower Bound Environments,” Economics Letters 118(1), 135–138.

Primiceri, G. E. (2005), “Time Varying Structural Vector Autoregressions and Monetary Policy,” The Review of Economic Studies, 72(3), 821-852.