The Covid-19 pandemic continues to cast a dark shadow over Europe. The health and economic crises are reflected in exceptionally weak forecasts for the economic growth in 2020.

Since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, 25 countries have together approved more than a thousand measures worth about EUR 3 trillion or about 20% of GDP. Most Independent Fiscal Institutions consider fiscal responses in their countries to be appropriate and well-targeted. Nonetheless, the adopted measures will have a substantial impact on public finances. According to IFIs’ recent macroeconomic forecasts, the budget deficits are expected to increase by 8% of GDP while public debt will rise by about 16% of GDP by the end of 2020.

This European Fiscal Monitor policy brief, of the activities of EU IFI and the expected impact on the government finances in the 24 EU member states2 and the UK up to September 2020. The monitor is based on a survey among EU IFIs3.

The Covid-19 pandemic continues to cast a dark shadow over Europe. The health and economic crises are reflected in exceptionally weak forecasts for the economic growth in 2020.

These forecasts show a marked deterioration compared to the forecasts before Covid-19, but also compared to the early forecasts after the outbreak. The projected real GDP growth for 2020 fell by an average 9% of GDP from 2% growth before the Covid-19 outbreak to a 7.5% decrease according to the latest forecasts. Some national Independent Fiscal Institutions (IFIs) responsible for the independent fiscal oversight at national level adjusted their spring forecasts downwards or noted that real developments are getting close to what was previously outlined as the most adverse economic scenario. It is currently unclear how the situation will evolve, given the recent rise in infections.

Since the Covid-19 outbreak, all European countries have taken fiscal measures to address the health crisis and limit the adverse impact on the economy. The amount4 of new fiscal measures has slowed down in the past three months, but the amounts announced over the summer are still substantial. Some governments extended their short-time work schemes and adopted new support measures for companies. Should the restrictions be prolonged or tightened, governments may well need to provide further fiscal stimulus.

This policy brief gives an overview of the activities of EU IFIs and the expected impact on the government finances in the 24 EU member states5 and the UK up to September 2020. The European Fiscal Monitor is based on a survey among EU IFIs6.

Most governments (20 out of 25 countries) implemented appropriate fiscal responses to the Covid-crisis, according to national IFIs. The latter found that the adopted fiscal measures were rapid, well-targeted and generally effective to reduce the adverse economic impact. Income and employment supports are assessed as being the most effective measures in containing the impact of Covid-19 restrictions on households and businesses. Nevertheless, many national IFIs indicated that liquidity measures had limited effect due to mistargeting and the complex bureaucratic procedures that delayed their implementation.

Only in three EU member states were the fiscal responses deemed excessive by at least one domestic IFI. Domestic IFIs considered the fiscal measures of two EU member states to be insufficient to counter the crisis.

Despite the fact that most IFIs considered the national fiscal responses to be appropriate, there were 17 IFIs that raised concerns about some aspects of fiscal policy. Their concerns mostly related to: i) measures targeting companies that did not set conditions concerning the viability; ii) measures categorised as response to Covid-19 pandemic that not were directly related to countering the crisis; iii) the absence of a medium- to long-term debt sustainability assessment; and iv) the removal of expenditure and debt thresholds for 2021.

Almost all IFIs raised concerns about the surge in public spending and the increase in public debt. More specifically, the IFIs deem it important that the measures do not stretch beyond the crisis and that the medium and longer-term fiscal implications are considered.

Following the activation of fiscal escape clauses at both national and EU level, countries introduced fiscal measures of unprecedented size.

Since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, 25 countries have together approved more than a thousand measures7 worth about EUR 3 trillion or about 20% of GDP. Most of these measures were part of the immediate response to the crisis and aimed to soften the economic contraction, such as liquidity measures for companies and expenditures to avoid unemployment. As most countries lifted the lockdown restrictions and some of the initial measures remain in place, fewer fiscal measures have been adopted in the past few months. Most of the measures adopted after the previous policy brief in June aim to support economic recovery and smooth the transition to the new normal (e.g. measures to support the reskilling of employees).

The 25 countries have spent around 6% of GDP and foregone about 1% of GDP in revenues, amounting to 7% of GDP. These measures, such as budgetary spending and tax reductions, contributed to an increase in the budget deficit, alongside the automatic rise in social spending and a fall in tax revenues. The main objective of these measures is to reduce the economic impact of the crisis and to avoid funding shortages.

The magnitude of the discretionary fiscal response is significant. Most countries have committed to spending measures amounting to around 6% of GDP and give tax relief for another 1% of GDP. Nearly all these measures are short-term, covering up to one year. This means that if the crisis were to last longer, the measures would have to be extended or renewed, increasing the amounts involved. Some 10 of the 25 countries surveyed have adopted medium-term discretionary measures amounting to about 0.3% of GDP on average. These are primarily capital investments and tax-rate cuts. In total, five countries8 have introduced open-ended packages with an estimated average size of 0.2% of GDP. Open-ended packages do not have a cut-off date or a spending limit, which means their size could increase, if need be.

In addition, they have taken up about 14% of GDP in liquidity measures. The liquidity measures consist of credit guarantees (11% of GDP), loans (2%) and tax deferrals (1%). Liquidity measures aim to facilitate the access of companies and the self-employed to working capital, while only having a limited immediate impact on the fiscal deficit.

Companies are the largest direct beneficiaries of all the different types of measures adopted. Indeed, about 17% of GDP in funds – mostly credit guarantees – were committed to companies. The remaining measures target households (2% of GDP), the public sector (1%) and other institutions (1%).

119 countries have also implemented budget savings. These are primarily re-allocations of budgetary and EU funds, increases in governmental reserves and local governments’ borrowing limits. Budget savings aim to mobilise and consolidate existing programmes to ensure sufficient funding of adopted fiscal stimulus and accelerate its implementation.

Some countries have adopted other measures to mitigate the economic consequences of Covid-19. These are mostly changes to legislation, budget reallocations and credit moratoria. In addition, some countries have facilitated the receipt of unemployment benefits and outlawed seizures and the eviction of tenants. In the domain of prudential regulation, some countries have also relaxed the capital requirements for banks, thereby easing the lending to temporarily constrained borrowers.

The Covid-induced fiscal measures and automatic stabilisers will have a significant direct budgetary impact. Although part of the measures run beyond the current fiscal year, the latest forecasts for this year already anticipate most of the fiscal implications of the national Covid-19 measures.

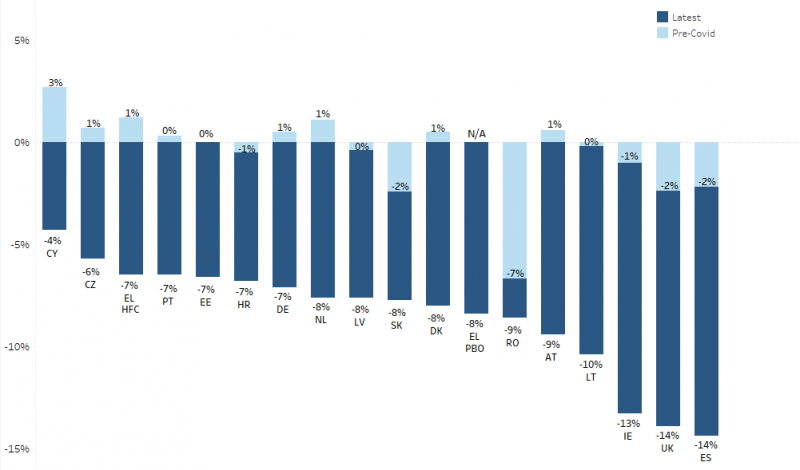

The pandemic has caused a major deterioration in the fiscal indicators across the board. According to the latest forecasts of national IFIs, the budget deficits in 2020 are expected, as of early September, to increase to 8.6% of GDP on average, from 0.5% of GDP before Covid-19 (see Figure 1). The latest forecasts for the 2020 budget deficits range from 4% of GDP in Cyprus to 14% in Spain. However, for most countries, the projections for the budget deficits range between 6% and 9%.

Compared to the pre-Covid-19 forecasts, Romania has by far the smallest increase (+1.9%) as its fiscal response was constrained by the Excessive Deficit Procedure launched in March 2020.

Figure 1. Projected budget balance (% of GDP)

Note: The figure above shows the projections of IFIs for the 2020 budget balance before Covid-19 and the most recent forecasts. For Greece (PBO) only the latest forecasts are available. The figures for Ireland relate to GNI rather than GDP.

Source: The Network of EU Independent Fiscal Institutions (2020).

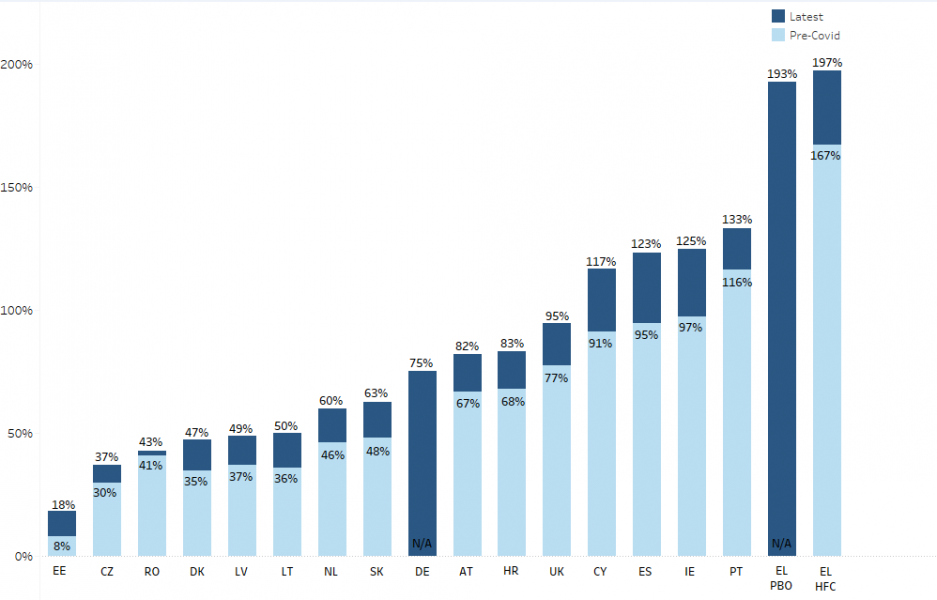

Covid-19 is likely to have an even bigger impact on public debt (see Figure 2). According to the latest forecasts the IFIs expect an increase in borrowing of about 16% of GDP on average by the end of 2020, from 66% of GDP before Covid-19 to 82% of GDP following the latest forecasts. The largest increase in debt-to-GDP ratio is expected in Spain (+28.5%). Austria (+15%), Croatia (+15%), Cyprus (+26%), Greece (+30%), Ireland (+27%), Portugal (+17%), Slovakia (+15%) and the UK (+17%) – all these countries forecast an increase in their debt ratio of more than 15%. Taking this increase into account, some 1110 countries are projected to exceed the debt ceiling of 60% in 2020, of which 8 countries11 were already well above the threshold before the Covid-19 outbreak.

Figure 2. Projected public debt (% of GDP)

Note: The figures above show the IFIs’ forecasts for public debt at year-end 2020 before Covid-19 and most recently. For Germany and Greece (PBO) only the latest forecasts are available. The figures for Ireland relate to GNI rather than GDP.

Source: The Network of EU Independent Fiscal Institutions (2020).

The increases in both the expected budget deficits and public debts will inevitably raise questions about long-term debt sustainability. In fact, most EU countries have already exceeded the now temporarily suspended Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) thresholds for budget deficit (maximum 3%) and public debt (60%). Many EU member states are likely to find themselves in the extended Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP) regardless of the prolongation of the General Escape Clause for 2021.

The daily activities of most IFIs continue to be affected by the Covid-19 pandemic. IFIs are experiencing increased workload, significant changes to content and changes in the publication deadlines.

There are ten IFIs that have conducted an evaluation of public spending in 2020 or are planning to do so. As of September 2020, only the Dutch Council of State and Spanish AIReF have published (intermediate) results12,13 of their spending review. The other publications will come through later this year. Four other IFIs decided to postpone their evaluation.

As new fiscal measures are adopted, EU IFIs are also closely monitoring the economic and fiscal situation. Some IFIs assessed and endorsed the Covid-19 related budget amendments.

The authors would like to thank Sander van Veldhuizen, Chair of the Network of European Independent Fiscal Institutions and Sebastian Barnes, Deputy chair of the Network for the review. The authors would also like to thank Beatriz Pozo (CEPS) as well as the members of the Network for their valuable contributions to this policy brief.

AT, BG, CY, CZ, DE, DK, EE, EL, ES, FI, FR, HR, HU, IE, LT, LU, LV, MT, NL, PT, RO, SE, SI, SK.

European Network of EU IFIs, 2020, Survey of European Independent Fiscal Institutions September 2020.

This EFM considers the committed or expected amounts; the actual amounts used may differ.

AT, BG, CY, CZ, DE, DK, EE, EL, ES, FI, FR, HR, HU, IE, LT, LU, LV, MT, NL, PT, RO, SE, SI, SK.

European Network of EU IFIs, 2020, Survey of European Independent Fiscal Institutions September 2020.

A fiscal measure is considered to be a single governmental initiative that falls under one detailed classification, targets one type of beneficiary and is adopted at one point in time. The size of a fiscal measure indicates the budgetary impact of discretionary measures and the maximum contingent liability for liquidity measures.

AT, DK, EL, ES, FI.

BG, CZ, DE, DK, EE, ES, FI, LT, LV, RO, SE.

AT, CY, EL, ES, DE, HR, IE, NL, PT, SK, UK.

AT, CY, EL, ES, HR, IE, PT, UK.