All opinions expressed here in this policy brief are our own and do not necessarily reflect those of Bank of Finland or the Eurosystem. This is an abbreviated version of our discussion paper Hukkinen and Viren (2025). We are grateful to John Cochrane for useful comments.

Abstract

Recent economic developments in Argentina give rise to several interesting observations about the workings and effects of economic policies. Of particular interest, of course, are the dramatic changes in inflation as a consequence of the economic policies of the newly elected President Javier Milei. Here, we briefly describe these policies and try to assess how much they contributed to this outcome. As a reference, we use indicators of monetary policy, which are conventionally considered to be of decisive importance in combating inflation. Although we cannot provide a formal test for the importance of different policies, it seems that policies which restored fiscal soundness were the decisive factor.

Argentina represents an interesting experiment in economic policies, given its history of failed economic strategies, low growth, high inflation, and repeated currency crises. Here we focus on the recent episode following November 19, 2023, when Javier Milei was elected President of the Republic. The striking aspect is the surprisingly rapid slowdown of inflation, which appears to lead to a permanent low inflation regime and a balanced growth of output.

The intriguing question is: why is that? Do these developments follow the general wisdom where credit is given to the Central Bank, so that inflation is said to be curbed by tight monetary policies, typically through higher interest rates? Or was it because a credible path of future fiscal balances was achieved by drastic reductions in government expenditures?

Clearly, these alternatives make a huge difference, not only because of different actors but also due to differing views on time horizons. With monetary policies, the focus has reduced to a kind of fine-tuning of interest rates at the level of basis points as reactions to changes in proxies of inflation expectations and individual commodity prices. With the fiscal view (interpreted according to the fiscal theory of the price level (FTPL), see Cochrane, 2023), everything boils down to the perceived ability of the government to service its debt, and thus, the time horizon is much longer, and relevant measures cannot be explained by mere decimals of the government deficit-to-GDP ratio. Thus, marginal changes in government expenditures and revenues do not matter unless we are in a scenario where government credibility is close to zero, i.e., when “a straw breaks the camel’s back.” Politicians are evidently happy with the monetary policy/central bank view: they can blame the central bank for the loss of price stability, whereas with the FTPL, they cannot pass the buck to third-party operators.

In the case of Argentina, inflation is a permanent visitor, and it is a bit hard to think that inflation is due to some monetary policy errors, repeated supply and demand shocks, or a perverse form of (inflation) expectations formation. Thus, one is tempted to consider more profound reasons for the continuous failure in preserving price stability, and it is hard to exclude the possibility that this failure stems from more general government failure, which in the first place shows up in excessive government deficits.

hen scrutinizing the data shown below, we strongly favor the “fiscal failure view” because of the following observations.

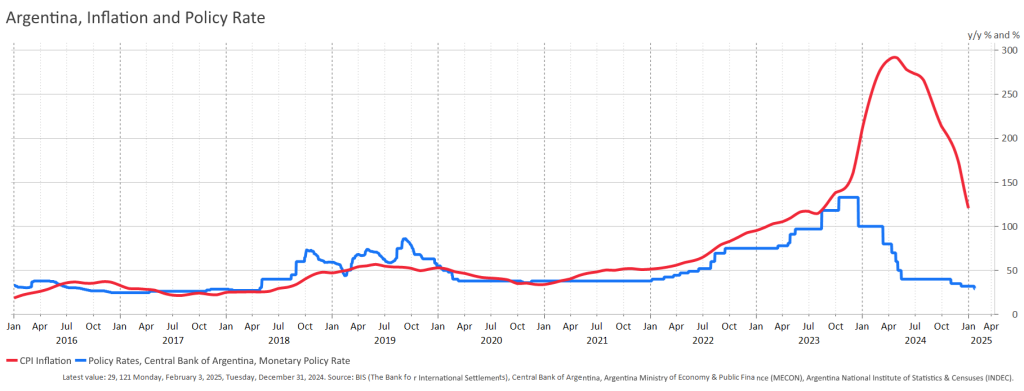

The Central Bank’s response to developments in inflation was simply too weak to reduce the inflation rate. Thus, the real interest rate stayed negative continuously after the whole Covid-19 period. In 2024, the values were notoriously low, coming close to -250 % (Figure 1). It seems that the Central Bank tried (and failed) to maintain some decency in the real interest rate but gave up on this idea quite early. There are no signs that high real rates would have caused a marked fall in output and a consequent fall in inflation.

Figure 1. Annual CPI inflation with the policy rate

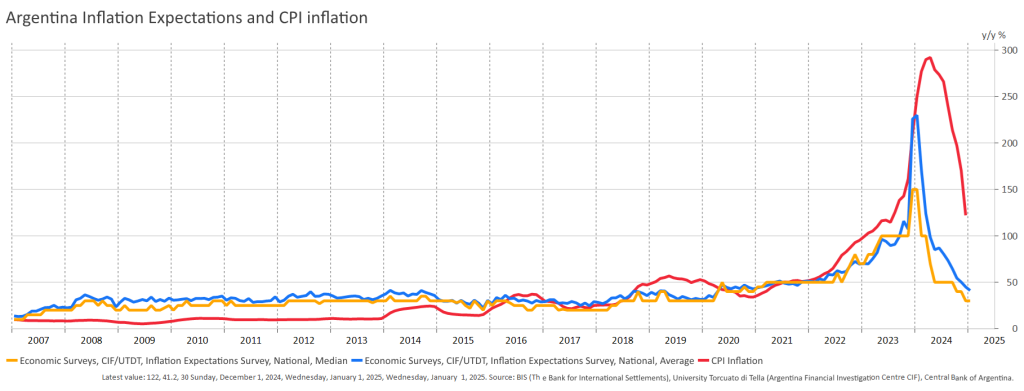

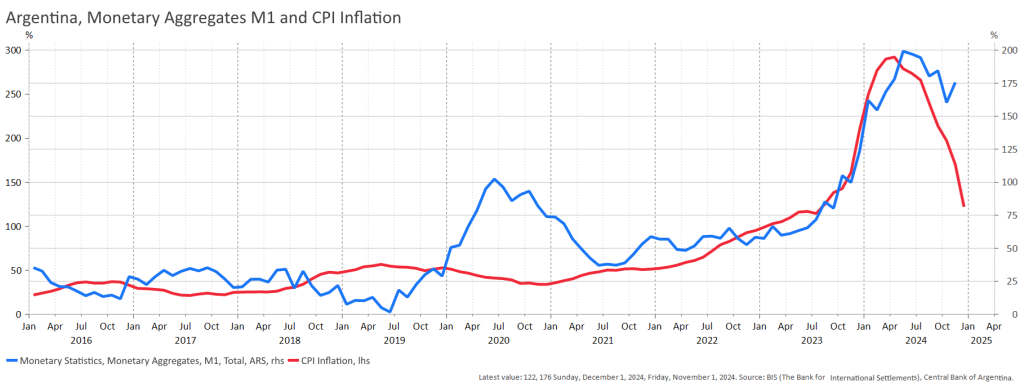

If we had a conventional New Keynesian Phillips curve as a point of reference, we would need a very sophisticated story for inflation expectations, a story that nobody could verify. The data we have on inflation expectations suggest that – in the same way as in most other countries – expectations fell short of actual values of inflation, and the duration of inflation was grossly underestimated. (Figure 2). If we focus on monetary aggregates, they all follow the same time pattern (see the graph for M1 in Figure 3), but there is no lead-lag relationship and, moreover, the growth rate of money is much less than the rate of inflation indicating a big fall in real balances.

Figure 2. Inflation and inflation expectations

Figure 3. Money supply and inflation

Note: The money supply growth numbers are much smaller than inflation. The graphs for M2 and M3 are very similar.

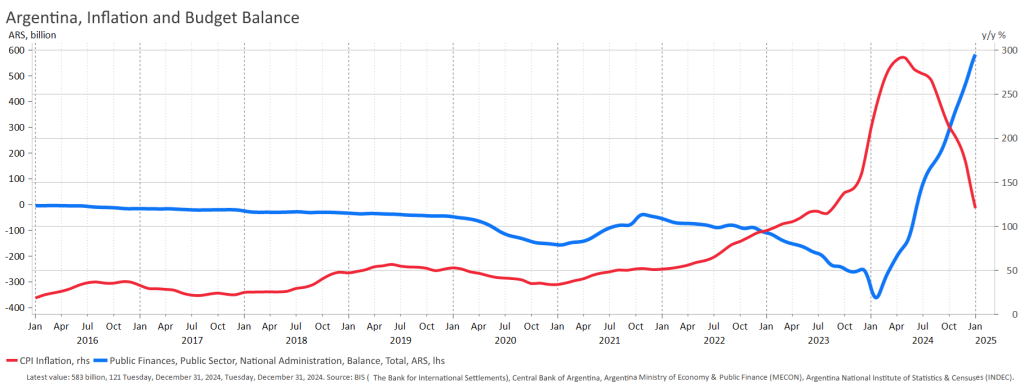

Things look quite different from the perspective of fiscal policy. Milei’s fiscal policy actions have clearly made a significant impact from a historical standpoint.

First, Milei made a strong commitment to permanently balancing government finances. Had he abandoned this commitment immediately after the elections, he would have become a “dead man walking,” and the entire movement or party would have collapsed.

Second, he achieved this balance through harsh measures, both legislative and operational. Perhaps the most significant action was the reduction of the government payroll (summarized in the timeline of events appendix). These cuts affected roughly one-third of the personnel in the central administration. Crucially, these actions were implemented immediately rather than being deferred as promises or future plans. As Alesina, Favero, and Giavazzi (2019) have shown, an expenditure-based approach is more effective than a revenue-based approach and may also be more credible than strategies that attempt to manipulate government transfers. Most decisions or laws regarding taxes and transfers apply for only one fiscal year and can be easily reversed, whereas reductions in public sector employment and the closure of government institutions are far more difficult to undo.

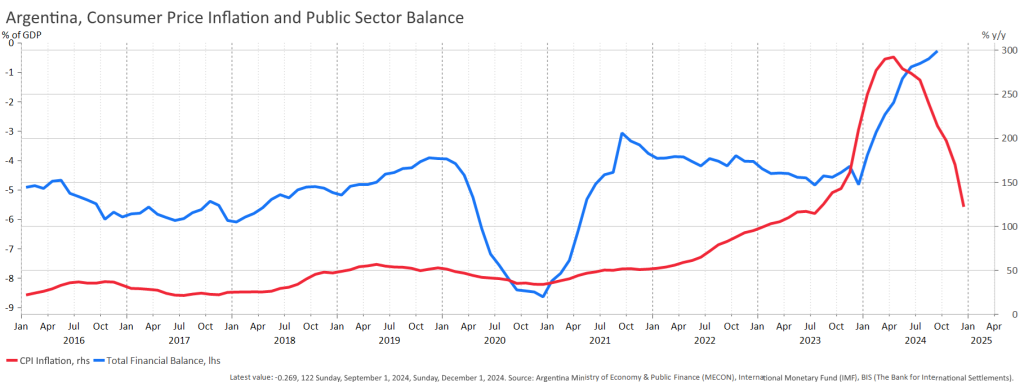

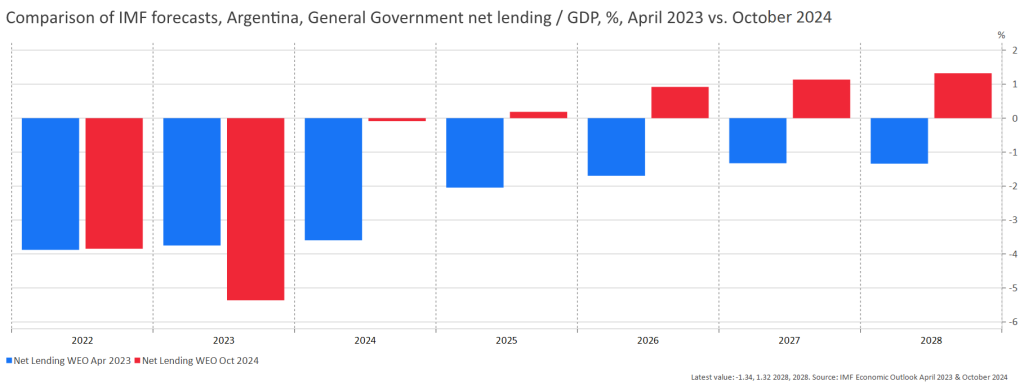

The data also show that inflation peaked just a couple of months after fiscal tightening, with no subsequent reversal (see Figures 4 and 5). Fiscal austerity is reflected not only in inflation trends but also in consumer confidence and in the IMF’s assessments of Argentina’s future fiscal balances (see Figure 6).

Obviously, one might ask why inflation began in 2023. The most apparent reason seems to be the general public’s loss of confidence in the government’s ability to service its debt. In 2023, GDP was declining at a rate of -1.6%, while in 2024, the growth rate was -3.5%, reflecting a drop in investment and government output. This makes it difficult to attribute changes in the price level to demand shocks unless we assume highly unusual parameter values for behavioral equations.

Figure 4. Inflation and net lending in pesos

Figure 5. Inflation and the net lending/GDP ratio

The very rapid recovery of total output toward the end of 2024 clearly calls for an explanation. One plausible explanation is the new economic regime, which brought price stability and a lower risk of financial and economic crises. Another explanation is the set of policies that liberalized markets, eliminated excessive bureaucratic burdens, and reduced barriers to trade (see the interview with Minister Federico Sturzenegger (2025)). These measures were intended to be permanent, and the scale of the legislative actions was unprecedented—roughly half of the regulations were simply scrapped, while the rest were simplified. This combination of institutional and legislative actions reinforced each other, further emphasizing the permanence of the change.

It is no surprise that, almost immediately, output began to rise, accompanied by lower unemployment, reduced poverty rates, and higher growth rates (see Hukkinen and Viren, 2025). The IMF’s predictions for future GDP growth now hover around five percent, up from just two percent in 2023. Growth had already accelerated in the latter half of 2024, with, for example, a monthly economic activity growth rate of 4.6% recorded in December 2024. Thus, there is no evidence of large multiplier effects that would have pushed Argentina into a severe depression. On the contrary, the data suggest that the multiplier has been negative rather than positive.

There are many possible ways to interpret this evidence. One compelling possibility is Lucas’s (2009) model of technology diffusion and trade, where “everything boils down to the adaptation parameter, which in turn reflects how well the market mechanism works and how many barriers to trade exist.” In a well-functioning market system, technology adaptation is a crucial driver of growth, accelerating progress in countries lagging behind the technology frontier—such as Argentina (see, for example, Gonzales and Nicolini, 2024). Perhaps the economic miracles of Germany and Italy during the 1950s and 1960s could also serve as examples of such a recovery.

Figure 6. Comparison of consecutive IMF forecasts

This paper provides illustrative material on recent developments in the Argentine economy after the newly elected president, Javier Milei, initiated an extensive set of government reforms. The outcome of these reforms is particularly interesting in relation to inflation: does the successful consolidation of government finances eliminate inflation even when monetary policy remains relatively passive? The data sends a clear message—successful fiscal reforms are crucial for achieving price stability. Needless to say, more rigorous empirical analysis is required to examine this key issue in economic policy.

Alesina, A., Favero, C and F. Giavazzi (2019) Effects of Austerity: Expenditure- and Tax-Based Approaches, Journal of economic Perspectives 33(2), 141-162. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.33.2.141.

Cochrane, J (2023) Fiscal Theory of the Price Level. Princeton University Press.

Gonzales, T. ja J. Nicolini (2024), “Argentina at a Crossroads”, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review 44(3): 2-15. https://doi.org/10.21034/qr.4432.

Hukkinen, J. and M. Viren (2025 What can we learn from Argentina’s new economic regime? ACE Discussion Paper 169. https://ace-economics.fi/discussion-papers/.

Lucas, R.E. Jr (2009), “Trade and the Diffusion of the Industrial Revolution”, American Economic Journal. Macroeconomics 1(1): 1–25, https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/mac.1.1.1

Federico Sturzenegger, F. (2025) On Chainsaw and Deregulation: The First Year of Javier Milei’s Presidency. Interview in the Markus’ Academy. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8b4SFDdAY_A

Data from figures comes, unless otherwise indicated from the Central Bank of Argentina https://www.bcra.gob.ar/varios/English_information.asp or from the National Institute of Statistics and Consensus (INDEC) of Argentina https://www.indec.gob.ar/indec/web/Institucional-Indec-QuienesSomosEng.

Timeline of events