Abstract

Russia’s aggression against Ukraine and the decision to grant candidate status to Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia have put enlargement back at the top of the EU’s agenda. While it is impossible to predict the exact budgetary impact of future enlargements —given the uncertainty around their timing and scope—it is crucial to anticipate it. While doing so, this paper challenges two widespread misconceptions. First, history shows that enlargement does not necessarily increase the size of the EU budget. This is always a political choice. Second, the impact of enlargement on the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and Cohesion Policy will differ significantly, with CAP facing the greatest challenges. This should prompt a strategic reflection on how to manage the accession of large, the mechanisms that could be activated to mitigate impacts, and potentially the need for CAP reform. Finally, to ensure a balanced debate, budgetary cost estimates must be weighed alongside the economic and strategic benefits of future accessions.

Russia’s aggression against Ukraine and the subsequent decision to grant candidate status to Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia has put enlargement back on top of the EU’s agenda. Including Türkiye (with whom accession negotiations have been at a standstill since June 2018), the EU now has a total number of ten candidate and potential candidate countries. Even if there is high uncertainty on the timing of future accessions, it is essential to anticipate future accessions and the implications for the EU budget.

Various studies provide estimates of the budgetary costs of integrating all or some candidate countries into the EU– see for instance Rant et al. (2020), Emerson (2022), Lindner et al. (2023), Darvas et al. (2024), Matthews (2024), Nuñez Ferrer et al (2024) and Rubio et al. (2025). These studies reveal the challenges posed by the next possible accessions and their impact on the EU budget, focussing on the costs. However, each estimate relies on a set of assumptions and methodological choices making them far from precise cost predictions. Furthermore, a strict focus on estimates based on the application of current eligibility rules denies the Union´s agency to adapt to future accessions. A look at past enlargements shows that the Union usually mitigates expected disruptions by introducing changes to eligibility rules, establishing transitional periods for new Member states to access EU funds, or capping ex-ante some spending programmes.

To foster a well-informed debate on the budgetary costs of future accessions, it is necessary to combine the results from new estimates with lessons drawn from the past about how enlargements were managed. Estimates should be transparent about the assumptions taken to calculate the costs of enlargements, particularly in distinguishing projections based on the application of existing rules from those shaped by ad hoc political assumptions, which can imply very different policy strategies – and hence costs- for adapting the EU budget to new accessions. While until recently, enlargement was not expected to be the major concern of the next Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) negotiations, the recent, rapid geopolitical shifts have dramatically increased the uncertainty about the timing and scope of future enlargements. This implies that flexibility will be key to accommodating the EU budget to different scenarios. Finally, to ensure a more balanced discussion, estimates of budgetary costs should be accompanied by assessments of the economic and broader benefits of future accessions.

Predicting the exact budgetary costs of enlargements is impossible. The final cost will be the result of existing rules, historical norms and, above all, political negotiations, which can only be guessed. Nevertheless, cost estimates play a crucial role in identifying the EU programmes most affected, understanding the potential distributional consequences for current Member States and the overall budget size as well as assessing the impact of different approaches to adapting the budget.

To estimate the potential budgetary costs of new accessions, one has to look at the rules determining the distribution of funds across Member States– particularly CAP and Cohesion Policy funds. However, these rules are not always clear. For Cohesion Policy, funding allocation follows a numerical formula – known as ‘the Berlin formula’1 – which has remained largely unchanged since the 2000s. This formula primarily considers regional per capita, national GNI per capita and population to determine the amount of funding each Member State receives.

In contrast, CAP allocations to Member States for 2021-2027 are set in current prices in the annexes of the CAP Regulation2. Pillar 1 CAP allocations, which finance direct payments to farmers, are loosely correlated with the amount of agricultural land. However, the per-hectare funding is not determined by a formula based on objective criteria, such as agricultural production, productivity levels, or disparities in farmers’ living standards. Instead, these allocations stem from historical political decisions, resulting in significant differences between countries. For instance, at the moment of acceding to the Union in 2024 and 2007, Central Eastern Countries were granted lower per-hectare payments compared to Member States, implying important differences in CAP pillar 1 aid intensity between Western and Eastern Member States. Since 2013, these disparities have been progressively reduced with the application of the so-called ‘external convergence’ principle, but they will not be fully eliminated by the end of the current MFF3. Pillar 2 CAP allocations, which support rural development, follow a cohesion-like logic— higher-income countries with more developed agricultural sectors receive a smaller proportion of funds relative to their agricultural land area. However, there is no clear formula guiding the distribution of funds4. As a result, there is no clear principle to determine how much CAP funding per unit of agricultural land future acceding countries would receive. The main guidance comes from the experience with previous enlargements.

The impact of accessions on non-allocated EU budget spending is even harder to predict. There is no legal obligation to increase this expenditure following an accession. In past enlargements, the Commission initially proposed raising this spending in proportion to the increase in the size of the Union’s GDP but, during the MFF negotiations, these amounts were subsequently reduced.

Estimating the impact of enlargement on EU budget revenues is equally complex. Since the largest source of revenue comes from GNI-based contributions, most studies assume that new members’ contributions will be relatively small, as they are proportional to national GNI. However, amounts collected from Traditional Own Resources (TOR) – customs duties on imports to the EU – represent roughly 10-12% of the EU’s revenues. When a candidate becomes a Member State, by changing EU borders, it automatically reduces the TOR collected by current Member States, while the new Member State begins collecting custom duties on extra-EU imports. Estimating the overall net effect is difficult, as it would require detailed data on trade flows between the EU and each candidate country, the level of trade integration and the volume of extra-EU imports entering through the candidate country.

1.1 Interpreting existing estimates

As mentioned above, the various studies that have estimated the budgetary costs of accessions differ in their assumptions and methodological approaches, leading to slightly different results5. The greatest variation arises in the estimation of additional CAP funds. One key factor is the parameter used to determine the level of CAP aid intensity—specifically, the euro amounts per hectare granted to new Member States. Some studies assume that new Member States will receive the same CAP aid intensity as those with the lowest existing aid levels (see Darvas et al. 2024; Rubio et al. 2025). Others interpret current CAP rules as maintaining the commitment to ‘external convergence,’ which would result in a full equalization of CAP aid intensities (see, for instance, Matthews 2024). In the latter case, the CAP costs of engagement are higher.

A second parameter is whether an overall ceiling is imposed on the CAP budget. Most studies do not impose any overall ceiling; they assume that current Member States will keep their CAP allocations and the overall CAP budget will increase to cover the extra CAP funds allocated to new Member States (see Emerson 2024, Lindler et al. 2024, Darvas et al. 2024 and Matthews 2024). This assumption implies a large increase in CAP spending when large agricultural candidates join the EU. Others assume that the overall CAP pillar 1 budget will remain constant in real terms despite accessions, similar to what happened in previous enlargement, and that extra CAP funds for new Member States will be offset by reductions of CAP allocations for current Member States (Rubio et al. 2025).

Apart from these differences in assumptions and methodological choices, several caveats should be considered when comparing estimates of budgetary costs of enlargements.

First, except for Nuñez Ferrer et al. (2024) and Rubio et al. (2025), all other estimates are static. They simulate changes in EU budget expenditures if candidate countries were to become full Member States today. This implies that they do not factor in the impact of developments in income per capita in both enlargement countries and Member States, which will affect eligibility for and hence the distribution of EU Cohesion Policy funds (Emerson 2023).

Second, none of the estimates factor in potential changes to Cohesion Policy or CAP eligibility rules in future programming periods, which could alter eligibility for funding.

Third, in the particular case of Ukraine, there is significant uncertainty regarding the country’s future territory, population, and GDP at the time of accession. Yet, most estimates assume that Ukraine will regain its territorial integrity and pre-war population after the end of the conflict and that it will not suffer a drastic and permanent GDP decline. An exception is Darvas et al (2024), which estimates the impact of Ukraine´s accession on the EU budget under two scenarios.6

Finally, the budgetary costs of enlargement should not be compared to today’s situation but to the cost of a non-enlargement scenario. In recent years, pre-accession support has been significantly reinforced with the adoption of three new Facilities – the Ukraine Facility, the Reform and Growth Facility for the Western Balkans and the Reform and Growth Facility for Moldova. In the case of the Western Balkans, for instance, the adoption of the Facility has resulted in a 40% increase in EU budget support to the region7. A credible EU commitment to enlargement requires maintaining the same levels of support in the future, provided candidate countries demonstrate a similar level of engagement. As for Ukraine, the country will need massive support for post-war reconstruction regardless of its membership status. In other words, even if there are no accessions during the next MFF, the maintenance of a credible EU commitment to enlargement will require higher budgetary costs than today.

A common misconception in enlargement debates is that the accession of poorer countries inevitably results in an increase in the EU budget. However, this is not necessarily the case. While accession of lower-income countries creates pressures to increase Cohesion Policy and CAP spending, the overall impact on the EU budget depends on how these costs are managed – for instance, whether transfers to new Member States are offset by reductions in CAP and Cohesion Policy allocations to existing Member States or by cuts in other EU expenditure categories. In addition, as the Union’s total GNI grows with the new Member States, an increase in absolute terms of the budget does not automatically translate into a higher budget-to-GNI ratio.

Looking at historical precedents, early rounds of enlargement did not always lead to EU budget increases. In particular, the 1986 Iberian enlargement significantly expanded the Cohesion policy budget and increased the CAP budget, despite the introduction of transitional periods, and safeguard clauses to mitigate the impact on agriculture expenditure (Matthews 2024). In contrast, the eastern enlargement in 2004/2007 occurred during a period of budgetary constraints and did not lead to an expansion of the EU budget. The share of Cohesion Policy remained stable at 0.45% of the EU’s GNI and the CAP’s share decreased despite the entry of ten new Member States with large agricultural sectors.

The management of CAP budget impacts during the 2004 Eastern enlargement offers valuable insights. Initially, the Commission assumed that the new Member States would not benefit from CAP Pillar 1 funds. However, during the accession negotiations, candidate countries successfully secured access to these funds, albeit with a gradual 10-year phasing-in period. Payments began in 2004 at 25% of their full value and gradually increased, reaching 100% between 2008 and 2013.

The European Council endorsed this decision but did not raise the CAP Pillar 1 ceiling for 2000-2007 to accommodate it as the additional amounts needed for 2004-2007 could be covered within existing margins. The issue of how to adjust the CAP budget after 2007 was resolved through a Franco-German deal, subsequently endorsed by the European Council (2002). The deal imposed an upper limit on CAP Pillar 1 spending for 2007-2013 in exchange for a freeze on CAP reforms until 2006 (Ruano 2003). Specifically, to contain CAP spending, it was agreed that annual CAP Pillar 1 expenditures for 2007-2013 would be maintained in real terms at their 2006 level, with nominal annual increases capped at below 1%.

Another misconception is that enlargements exert similar pressures on Cohesion Policy and CAP spending. If we assume that current eligibility rules remain unchanged—or undergo only minor adjustments in future programming periods—the accession of new countries presents very distinct challenges for cohesion policy and CAP.

In Cohesion Policy, an automatic capping rule limits funding receipts to a maximum of 2.3% of GDP for the poorest Member States8.

Given that all enlargement countries have very low GDP levels (for instance, Ukraine’s GDP is estimated by the IMF at USD 189 billion—just over half of Romania’s), this cap significantly restricts the total Cohesion Policy funds they can receive. This has two key implications. First, contrary to some concerns, future accessions will not drastically increase the overall Cohesion Policy budget. Rubio et al. (2025) estimate that under a scenario (‘big bang’) in which the six Western Balkan countries, Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia join the EU in 2030, Cohesion Policy budget would only increase by EUR 8.7 billion per year compared to a no-enlargement scenario.

Second, the automatic capping rule also results in new Member States receiving relatively low amounts of Cohesion Policy funds. According to Rubio et al. (2025), in a ‘big bang’ scenario, four new Member States—Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia, and Kosovo would receive less total funding per capita than the 13 Member States that joined after 2004.

Another important consideration is that Cohesion Policy fund allocation is based on a region’s or Member State’s relative economic standing compared to the EU average, measured by GDP per capita for regions and GNI per capita for Member States. Since the accession of poorer countries lowers the EU’s average GNI/GDP per capita, some current EU Member States and regions may shift eligibility categories and receive less Cohesion Policy funding—an effect known as the ‘statistical effect’.

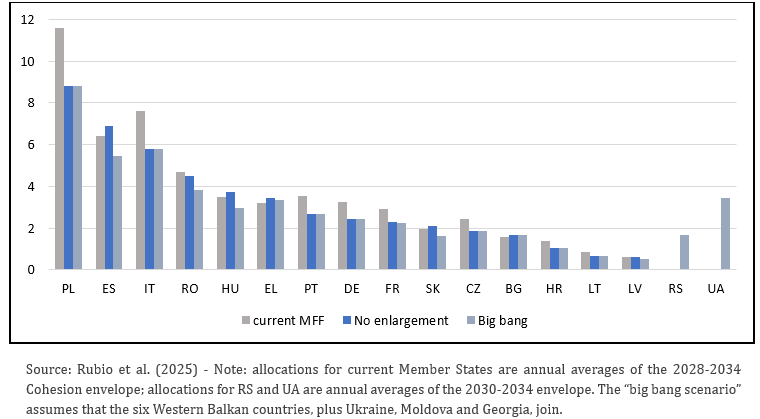

Specifically, Rubio et al. (2025) find that, in a ‘big bang’ accession scenario, the EU’s GDP per capita would decrease by roughly 10%. This would result in various current Member States receiving less Cohesion Policy funds than in a scenario without accessions. The largest declines would occur in Spain, Romania, Hungary, Slovakia and Latvia, which would suffer reductions of between 15%-22% of their national cohesion allocations compared to the no-enlargement scenario. Meanwhile, some countries, such as Poland, are projected to receive lower Cohesion Policy allocations in the next programming period regardless of enlargement due to their stronger economic growth than the EU average (see Figure 1).

In contrast to Cohesion Policy, CAP rules do not include an automatic capping mechanism. In consequence, without an explicit political decision to limit the overall CAP budget, the accession of a major agricultural country like Ukraine may entail a substantial increase in CAP spending. Specifically, if no upper ceiling is imposed on the overall CAP budget and Ukraine is granted a similar amount of CAP funds per hectare as the current Member States the CAP budget will increase by 22-25% with variations explained by the parameter used to determine Ukraine’s CAP aid intensity (Darvas et al. 2024, Matthews 2024).

Figure 1. Cohesion policy allocations: current allocations (2021-2027) vs estimated allocations 2028-2034 under a no enlargement and a ‘big bang’ scenario, first 15 EU27 beneficiaries plus Serbia and Ukraine (annual average, constant prices in EUR billion)

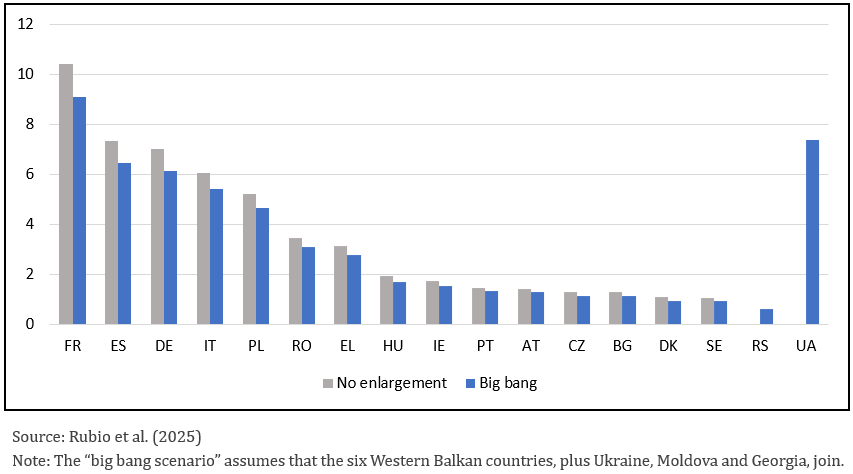

By contrast, Rubio et al. (2025) assume that the current CAP Pillar 1 budget is maintained in real terms and that new Member States are granted similar CAP aid intensity as those current Member States receiving lower CAP amounts (that is, Member States that joined after 2004). In this case, CAP allocations for EU27 would have to be cut by 15% on average to maintain the overall budget within the ceiling. The reductions would be more pronounced for countries such as France or Spain (-18%), which receive a higher percentage of Pillar 1 funds with respect to the total CAP allocation9 (see Figure 2). Importantly, by keeping CAP fixed in real terms and given the expected GNI growth, this scenario would liberate resources that can be used for other priorities.

The comparison of the assumptions and the differences in the associated estimates suggests the need for an informed debate on how to accommodate the policy to the accession of Ukraine. The prospect of expanding the overall CAP budget will be firmly opposed by net contributors, whereas significant cuts to national CAP allocations look unpalatable for large CAP beneficiaries. As in past enlargements, the final impact will be probably mitigated by imposing transitionary phase-in periods and/or granting new Member States a less advantageous CAP access. However, it should be noted that none of these strategies provides a lasting solution. Transitional periods do not avoid the cost of enlargement, they simply push them into the future. Past experiences show that once in the Union, new Member States use their negotiating power to improve the conditions agreed upon in accession Treaties and progressively obtain the same treatment as ‘old’ Member States. A more permanent solution would be to define a new allocation principle to distribute CAP pillar 1 funds across Member States. For instance, Pillar 1 funds could be distributed across Member States based on the amount of agricultural land managed by farms below a defined size threshold rather than eligible agricultural land area. This would reduce the amount of CAP funds for Ukraine, given the substantial amounts of land managed by large agro-holdings (Matthews 2024).

Figure 2. CAP allocations: estimated 2028-2034 allocations under a no enlargement and a ‘big bang’ scenario, first 15 EU27 beneficiaries plus Serbia and Ukraine (annual average, EUR billion)

This next round of enlargement faces considerable uncertainty. Significant and persistent challenges to democracy and the rule of law in most candidate countries, as well as the ambiguity around the Union´s willingness and capacity to enlarge, make it difficult to imagine a rapid accession process. In her confirmation hearing at the European Parliament on November 11th 2024, the Commissioner for enlargement, Marta Kos, claimed that only two small Balkan countries – Montenegro and Albania – seemed ready to integrate the Union in the coming years. If this were the case, the impact on the EU budget would be negligible. According to Rubio et al. (2025) estimates, for instance, Montenegro’s accession would result in a net cost of approximately EUR 0.13 billion for the EU27.

However, the deterioration of the geopolitical landscape since early 2025 due to the new US administration and the new turn of the war in Ukraine are changing the debate about the accession of Ukraine. Commission’s president Von der Leyen explicitly indicated that Ukraine could accede in 2030, or even before. This makes a scenario of enlargement, including Ukraine, during the next MFF no longer unimaginable.

A corollary of that is that the EU budget will need a big dose of flexibility to adapt to different possible enlargement scenarios. If a couple of small countries access the Union before 2034, the necessary funds could be covered within existing margins without reopening the MFF. To accommodate this relatively straightforwardly, there should be sufficient margins of unallocated commitments in key headings (e.g. cohesion, CAP). On the contrary, if a larger enlargement is foreseen in the following five or seven years, it might be worth exploring the possibility of establishing a shorter, 5-year MFF (ending in 2032) or establishing a special reserve for ‘accession-related costs’ over and above the MFF. Such reserve could be modelled on the reserve established in the 2000-2007 MFF to cover the costs of the Eastern enlargement. As this reserve, the extra funds would be mobilised through qualified majority voting in the Council, avoiding the possibility of some Member States blocking the decision. However, the establishment of reserves requires clear assumptions on the timing, scope of accessions and the result of accession negotiations. Therefore, a reserve may only be advisable if there is clarity about the timing and scope of new accessions.

As of today, predicting the exact cost of enlargement is impossible, primarily due to the uncertainty surrounding both the timing and scope of the next enlargement. However, unless the structure of the budget is entirely overhauled, there is little doubt that CAP and Cohesion Policy will face serious challenges. However, it will not be impossible to deal with them. Capping and transition periods could be activated to mitigate unwanted impacts.

In this respect, the experience of past enlargements is crucial to dispelling misconceptions that continue to riddle the enlargement debate. Two are particularly important. First, the size of the MFF is always a political choice, and enlargements do not necessarily lead to a greater EU budget; this was the case in 1986 but not in 2004. Second, if current rules are maintained, the impact of enlargement on CAP and Cohesion will differ significantly. While existing Cohesion Policy rules will contain the impacts of new accession, CAP will face the most critical pressures. This should prompt a strategic reflection on how to manage the accession of a large country, the mechanisms that could be activated, and the broader need for CAP reform — not only to accommodate future enlargements but also to adapt the policy to evolving priorities and challenges.

Finally, it is important to recognise that assessments of the EU budgetary costs of enlargement do not reflect the full range of potential economic and geopolitical implications. Enlargement can bring significant benefits for the Union in terms of security and political stability, greater market opportunities and reduced import dependency in critical sectors. While estimating these benefits is even harder than estimating the net EU budget costs, they should be a key part of any informed debate on the impacts of enlargement.

Darvas, Z., M. Dabrowski, H. Grabbe, L. Léry Moffat, A. Sapir and G. Zachmann (2024) The impact on the European Union of Ukraine’s potential future accession, Report 02/24, Bruegel.

Emerson, M. (2023). The Potential Impact of Ukrainian Accession on the EU’s Budget – and the Importance of Control Valves. RKK/ICD International Centre for Defence and Security, September 2023.

Lindner, J., Nguyen, T. and Hansum, R. (2023) What does it cost? Financial implications of the next enlargement, policy paper, Jacques Delors Centre, December 2013.

Matthews, Alan (2018), The CAP in the 2021-2027 MFF Negotiations, Intereconomics, Vol 53, Num 6 · pp. 306–311.

Matthews, Alan (2024) Adjusting the CAP for new EU members: Lessons from previous enlargements. SIEPS publication, September 2024.

Nuñez Ferrer, J., Schreiber, M. and Moreno, G. (2024) Furthering cohesion in an enlarged Europe. Impacts of enlargement on regional Cohesion Policy allocations, study, Conference of Peripheral and Maritime Regions (CPMR).

Rubio, E., C. Alcidi, R., Hansum, T. Akhvlediani, Iain Begg, J. Lindner and B. Couteau (2025), Adapting the EU budget to make it fit for the purpose of future enlargements, study requested for the Budgetary committee of the European Parliament.

The allocation formula for 2021-2027 is included in the Annex of the Common Provisions Regulation (Annex XXVI).A summary can be found in the European Court of Auditors (2019), Allocation of Cohesion policy funding to Member States for 2021-2027, Rapid Case Review, March 2019.

Annex V (Pillar 1) and Annex XI (Pillar 2) of Regulation (EU) 2021/2115 of 2 December 2021 establishing rules on support for strategic plans to be drawn up by Member States under the common agricultural policy (CAP Strategic Plans).

The external convergence principle was established in 2013 and maintained for the period 2021-2027. On the basis of this principle, Member States receiving amounts per hectare below 90% of the EU average should see their national envelopes progressively increased until closing half of the existing gap to 90%. The Member States’ allocations for direct payments in the Regulation 2021/2115 are calculated on this basis.

It is worth noting that in both the 2014–2020 and 2021–2027 MFF negotiations, CAP Pillar 2 national allocations were finalised at the last minute by the European Council and functioned as an “adjustment variable” to secure agreement on the overall MFF (Matthews 2018).

Looking at the net EU budget cost resulting from the accession of all nine enlargement countries except Turkiye the estimates range from EUR 14.7 billion (Rubio et al 2025) to EUR 26 billion per year (Darvas et al 2024).

Darvas et al (2024) distinguish between a baseline scenario (assuming territorial integrity and the economy and population developing according to 2020 projections) and an alternative scenario (assuming Ukraine’s agricultural land is reduced by 20 percent and there is a permanent decline in Ukraine’s GDP and population by 20 percent).

European Court of Auditors (2024), Opinion 01/2024 concerning the proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on establishing the Reform and Growth Facility for the Western Balkans, 7 February 2024.

Annex XXVI, Article 10a of the Common Provisions Regulation.

The reason being that, in our model, CAP pillar 2 is not capped. Hence, those countries receiving a higher percentage of pillar 2 CAP funds will experience a less pronounced decline in their overall CAP allocations.