Abstract

Financial education can influence the level of financial literacy, and political incentives can shape financial education policies. Political activism in financial education can be motivated by concerns over financial instability. By using financial education narratives as a proxy for political activism among European Parliament politicians from 1997 to 2024, we find that financial instability cases matter in explaining activism.

The importance of financial education (FE) is universally recognized. Financial education can help enhance financial literacy by enhancing micro knowledge (OECD 2015) and macro performances, including financial stability (Guiso 2010, Sapienza and Zingales 2012, Hastings et al. 2013). This relevance explains the policy focus on these issues. But: Is the political relevance of FE policies consistent with the abovementioned importance of financial literacy in the scientific debate?

Despite the introduction of active FE policies by some governments, in general their actual design and implementation is quite heterogeneous. Such heterogeneity can be explained using a theoretical political-economy framework (Guerini et al. 2024): the politician’s level of activism in FE is positively associated with instability risks, given other political gains and costs due to financial-illiteracy. Uncovering the political drivers that shape the provision of FE, zooming on financial (in)stability, and using text analysis, is the aim of our empirical research (Borghi et al. 2014). Reviewing the existing literature on financial literacy (Lusardi and Mitchell 2024) it is evident that so far economic analysis completely overlooked the role of political preferences.

The specification that explains the political activism can be motivated by three different hypotheses. In general, politicians may recognize that inaction in FE is costly, as it increases the likelihood of financial instability, particularly if citizens are influenced in their political choices by psychological group dynamics resulting from banking shocks (Favaretto and Masciandaro 2022). Moreover, politicians acknowledge that constituencies can exist both in favor and against FE. On one side, some citizen constituencies may view FE policies as a positive social investment (Buratti and D’Ignazio 2023). On the other side, some constituencies may view these policies as useless or costly, or even view financial illiteracy as beneficial. Financial illiteracy increases the activities of unskilled, unfair or illegal actors. If financial producers who gain from interacting with naïve citizens as unskilled/unfair actors, they will prefer financial illiteracy (Griffin et al. 2023, Bian et al. 2023).

With the goal to use political voices on financial education as a metric for activism, the first question to address is the identification of both the sender and the devise (Ferrara et al. 2022).

Regarding the senders, we focused on the European Parliament (EP), instead of national Parliaments, for at least three reasons. Firstly, in general, in the recent years, and specifically in the financial education field, the supranational organizations has been the mechanism to put pressures on national governments to implement policies (OECD 2015).

Secondly, in the specific case of the EP, European Union, the literature on bottom up politicization in Europe (Bressanelli et al. 20201) suggested that national political pressures provide politicians with new opportunities to politize issues at the European level, transforming the Parliament in a catalyst for domestic preferences, and triggering in turn a reaction from the EU forum to the national legislators. It is a matter of fact, after the adoption of the Lisbon Treaty (2009), the EP has been even transformed in a co-legislator, influencing the legislative process both at the European and national levels (Burn 2021). Finally, the selected sample allows to investigate preferences that vary not only along different political dimensions, but also considering different countries (Ferrara et al. 2022). All in all, the EP perimeter represents a bigger and more rich information set, that on top it is likely to include the preferences of the national Parliaments as sub-sets.

Regarding the device, the advantage of using speeches from the Parliament (Fraccaroli and Giovannini 2020, Fraccaroli et al. 2022a, Ferrara et al. 2022), rather than media coverage, allows us to directly access the original statements made by MEPs, ensuring we capture their genuine positions and priorities. Alternatively, an indirect channel can be used: media coverage. Yet, media coverage suffers the shortcomings which characterize any indirect device. In our case, it has been explicitly highlighted that during the hearings that motivated the speeches, media can be considered part of a heterogeneous audience (Fraccaroli et al. 2022b), that, in conveying the political messages, can distort them. By analyzing directly the speeches, we can better understand the true level of importance that politicians place on the issue, free from media interpretation or bias.

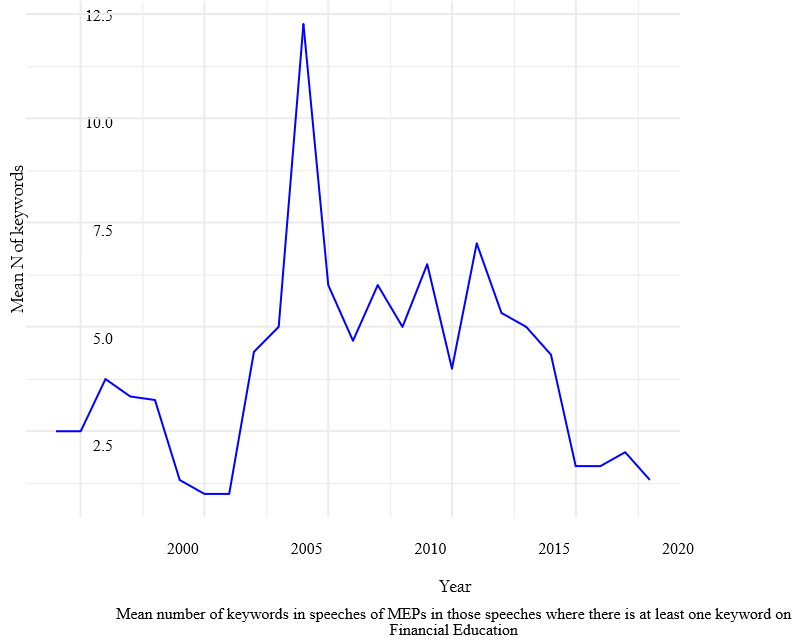

The descriptive analysis (Figure 1) reveals that discussions about FE among MEPs peaked during the 2008 Great Recession, and then remained consistently high during the following European Sovereign Debt Crisis. This trend suggests that politicians focus more on financial markets and institutions during times of financial crisis. Yet, this might introduce a bias into the analysis, capturing an effect not specifically related to FE. However, it is beneficial that we distinguished the topic of FE from that of financial stability, which was much more prominent during peak periods.

Figure 1. European Politicians: Voice on Financial Education

Then, to test the association between political activism and financial instability, we consider a dataset composed by the speeches pronounced by different MEPs speakers in the period 1999-2023.

We estimate the following empirical model using Pooled OLS with standard errors clustered at the politician level:

![]()

where FEi is the level of FE activism in speech i, using two different methodologies to build up it. Crisisi is a dummy variable taking value 1 if the speech was delivered during a financial crisis period. To obtain an objective measure of financial crisis years, we employ the European financial crisis database provided by the European Systemic Risk Board (Duca, 2017). Electioni is a dummy variable indicating the year of EU Parliament elections and Controls includes MEP speakers’ characteristics, such as country, gender and political affiliation, and a time trend.

Our main regressor considering financial crises is statistically significant for both the specifications of FE activism. We further perform a bunch of robustness checks, including the use of instrumental variables. All the supplementary robustness check further supports our central result: using FE narrative as a proxy for activism of the politicians of the European Parliament in the period 1999-2024, we found that financial instability cases matter in explaining political activism.

In future research, three intertwined directions can be explored. Firstly, our methodology can be used to explore other geographical settings, considering that both in OECD countries – including the United States – and in non OECD countries policymakers are active in the financial education area. Secondly, here the text-related quantitative measures have been implemented using simple indexes and the “dictionary approach”. The exploration could be extended applying the “sentiment analysis”, as well as the more complicated “word embedding.” Finally, the results obtained using the speeches of MEP as our metric can be expanded in two directions, exploring on the one side the speeches of the Members of national Parliaments, and using on the other side the media coverage as a proxy for the political voice.

Bian B., Pagel M. and H. Tang (2023), “Consumer Surveillance and Financial Fraud,” NBER Working Paper Series, n.31692.

Borghi E., Masciandaro D. and A. Papini (2024), “European Politicians and Financial Literacy Activism: Does Financial (In)Stability Matter?”, Economics Letters, forthcoming.

Bressanelli E., Koop C. and C. Reh (2021), “Actors under Pressure: Politicisation and Depoliticisation as Strategic Responses”, in E. Bressanelli, C. Koop and C. Reh (eds), Strategic Responses to Domestic Contestation. The EU between Politicisation and Depoliticisation, Routledge, London, 1-13.

Buratti G. and A. D’Ignazio (2023), “Improving the Effectiveness of Financial Education Programs. A Targeting Approach”, Bank of Italy, Occasional Paper Series, n. 765.

Burns C. (2021), “In the Eye of the Storm? The European Parliament, the Environment and the EU’s Crisis, Journal of European Integration, 41(3), 311-327.

Duca, M. L. (2017), “A New Database for Financial Crises in European Countries: ECB/ESRB EU crises database”, mimeograph.

Favaretto F. and D. Masciandaro (2022), “Populism, Financial Crises and Banking Policies: Economics and Psychology”, Scottish Journal of Political Economy, 69(4), 441-464.

Ferrara F., Masciandaro D., Moschella M. and D. Romelli, (2022), ”Political Voice on Monetary Policy: Evidence from the Parliamentary Hearings of the European Central Bank”, European Journal of Political Economy, 74, 102143.

Fraccaroli N. and A. Giovannini (2020), “Central Banks in Parliaments: A Text Analysis of the Parliamentary Hearings of the Bank of England, the European Central Bank and the Federal Reserve”, ECB Working Paper Series, 2442.

Fraccaroli N., Giovannini A., Jamet J-F. and E. Persson (2022a), “Ideology and Monetary Policy. The Role of Political Parties’ Stances in the ECB’s Parliamentary Hearings”, European Journal of Political Economy, 74, 102207.

Fraccaroli N., Giovannini A., Jamet J-F. and E. Persson (2022b), “Does the ECB Speak Differently when in Parliament?”, Journal of Legislative Studies, 28(3), 421-447

Griffin J.M., Kruger S. and P. Mahajan (2023), “Did FinTech Lenders Facilitate PPP Fraud?”, Journal of Finance, 78(3), 1777-1827.

Guerini C., Masciandaro D., Papini A., (2024), “Literacy and Financial Education: Private Providers, Public Certification and Political Preferences”, Italian Economic Journal, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40797-024-00287-1.

Guiso L. (2010),”A Trust-Driven Financial Crisis: Implications for the Future of Financial Markets”, EUI Working Paper Series, n. 7.

Hastings J.S., Madrian B.C. and W. L. Skimmyhorn (2013), “Financial Literacy, Financial Education, and Economic Outcomes”, Annual Review of Economics, 5, 347-373.

Lusardi A. and O.S. Mitchell (2024), “Financial Literacy and Financial Education: An Overview”, CEPR Discussion Paper Series, n.19185.

OECD (2015),”National Strategies for Financial Education OECD/Infe Policy Handbook”, https://www.oecd.org/finance/National-Strategies-Financial – Education-Policy-Handbook.pdf.

Sapienza P. and L. Zingales (2012), “A Trust Crisis”, International Review of Finance, 12(2), 123-131.