Despite the progress of the recent decades, the underrepresentation of women in decision-making positions is still a widespread phenomenon. Yet women’s empowerment is a top priority of institutions and firms, not only because of descriptive representation, but also because gender balance in decision-making positions may be associated to a different style of leadership and a different agenda. Using a new large dataset for 103 countries over the period 2002-2016, we document the evolution of the presence of women in monetary policy committees of central banks and their role in monetary policies. We show that a higher share of women on the central bank board is associated with a higher interest rate and that women in central banks have a more hawkish attitude, i.e. they are more aggressive in fighting inflation.

Despite the progress of the recent decades, the underrepresentation of women in decision-making positions is still a widespread phenomenon. According to Catalyst2, women represent only 30% of senior management in the European Union and 29% in North America. Among the largest publicly listed companies in the European Union (EU-28) in 2020, only 19.3% of executives and 7.9% of CEOs are women. In the US, there are still nearly 13 companies run by a man for every company run by a woman. In politics, only in 9 countries out of 153 there is a woman Head of State and only in 13 out of 193 a head of Government (IPU, 20213). The global share of women in national parliaments is 25.5 per cent (IPU, 2021).

Yet women’s empowerment is a top priority of institutions and firms. Not only there is an issue of descriptive representation but also of substantial representation. In fact, gender balance in decision-making positions may be associated to a different style of leadership and a different agenda (Profeta, 20204).

In business, recent analyses which exploit the introduction of board gender quotas find that the presence of women on boards has positive effects on the selection of board members (male and female), with an increase of the level of qualifications of all members (see Ferrari et al., 20215 for the case of Italy). The effects on performance are less conclusive, but most of the rigorous studies seem to suggest a null, or positive effect (see Profeta, 2020 for a review). Another important outcome related to the presence of women in decision-making positions is the policy agenda. The presence of women in politics, for example, has been associated to more effectively voicing “women’s interests” and influencing policy outcomes (see Hessami and Lopes da Fonseca (2020)6 for a recent review).

Monetary policy committees of central banks decide monetary policies, which are crucial for the economic situation of a country. The presence of women in these committees has been historically quite limited. However, a small but increasing number of women have risen even to the top of central banks: in recent times, we remind Elvira Nabiulina in Russia, Karnit Flug in Israel, Janet Yellen in the US and Christine Lagarde at the European Central Bank. For most central banks around the world, the main instrument of monetary policy is the short-term interest rate, at least until the financial crisis of 2008. Central banks make their decisions based on the current interest rate and on the expected deviations of the inflation rate and the output gap. The nature of the decision reduces the endogeneity concerns, which typically arise when we assess the relationship between the presence of women in decision-making positions and outcomes. In this context and given the recent trends and the relevant impact of monetary policy on the economy, the context of monetary policy becomes particularly interesting to investigate the role of women in decision-making positions.

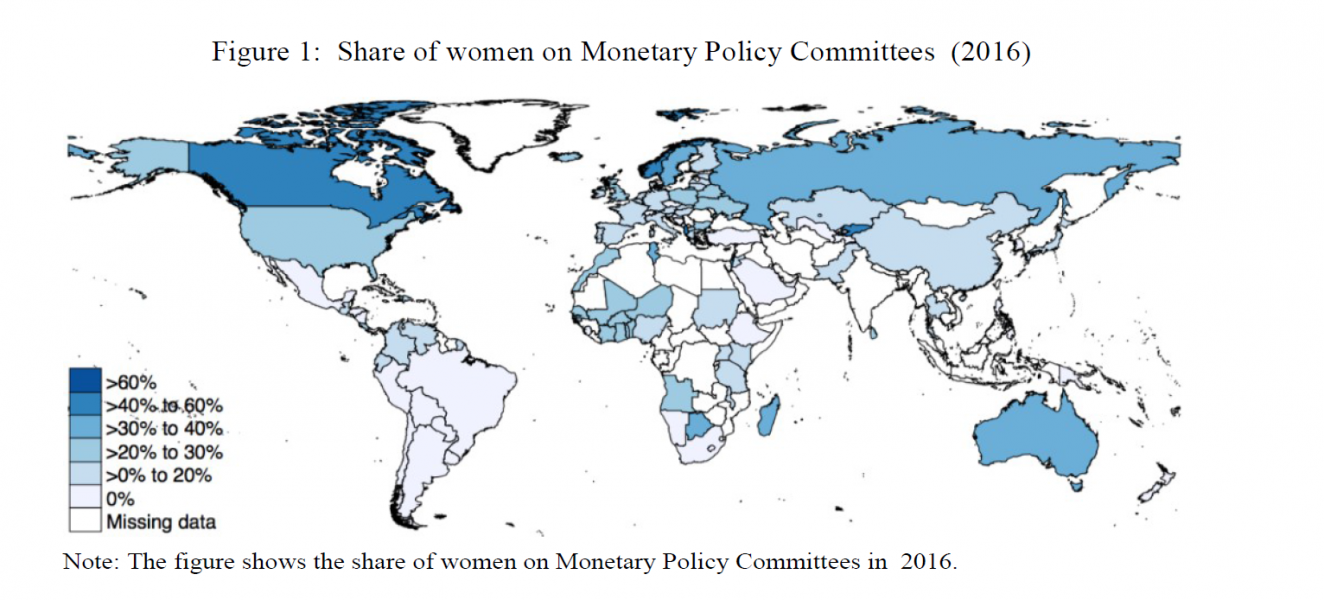

In a joint recent paper with Donato Masciandaro and Davide Romelli (Masciandaro et al., 20207), we construct a new large dataset on the presence of women on central banks monetary policy committees for 103 countries over the period 2002-2016. The dataset delivers a complete picture of the gender composition of central bank boards (see figure 1): the average share of women on on monetary policy committees is 14%. The top performer countries are Canada, Sweden, Serbia and Bulgaria with around 55-60% of women. The increase in the share of women during the considered period is substantial, from 11% in 2002 to 16% in 2016. The average size of the board remains at around 7 members. Women governors or deputy show a similar trend, increasing from 9 to 16%. The largest increase in women board members was in North America. Middle-East and North Africa, while Europe, Central Asia and Sub-Sahara Africa experienced a small contraction in women’s representation.

Figure 1

Source: Masciandaro et al. (2020)

We also find that central banks with no women on the board saw little change in gender representation over the decade considered. Over the period 2002-2016, 20% of the countries in our sample never appointed a woman to their monetary policy committee, while in any given year around 50% of the countries have no women.

When we use our dataset to investigate the determinants of the presence of women, we find that a variable which is positively related to the share of women in monetary policy committees is the staff gender ratio reported by the Central Banking Directory (2016), which provides information on the share of women among the total number of employees of central banks for the period 2012-2015. This suggests that central banks with overall more women employees have a higher female representation on boards as well. Other variables, including the gender gap index (World Economic Forum) are not significantly associated with the presence of board women members. In other words, the general level of gender inequality in the country seems not to be related to women’s representation in central banks.

We then use our dataset to analyze the relationship between the presence of women on boards of central banks and the monetary policy decisions. To isolate the effects of gender heterogeneity on policy decisions, we estimate a forward-looking Taylor rule that relates the target policy rate to deviations of expected inflation and output, and we augment it to include the share of women board members and its interaction with the inflation rate. We perform several estimations with different methodologies. Our results show that, for the same level of inflation, a higher share of women on the central bank board is associated with a higher interest rate. In terms of magnitude, an increase of one percentage point in inflation results in an interest rate that is 30 basis points higher in a central bank with a 50% share of women members compared to the rate with a 10% share of women. This suggests that women in central banks have a more hawkish attitude, i.e. they are more aggressive in fighting inflation. In other words, the presence of women in central bank boards can be a signal of prudence in implementing monetary policy actions.8

Our results are in line with more general results of research on different traits of men and women, which translate into different style of leadership and action when they make decisions. In particular, results are consistent with women being more risk-averse than men and taking more conservative decisions. This result is typically obtained in experimental settings and it applies to the general population, while it is not obvious to confirm it when we consider the highly selected group of women in decision-making positions (see Profeta, 2020 for a review). Yet we provide evidence that women’s empowerment does affect the policy and risk aversion may play a significant role in a context of real decision-making.

This policy brief is based on my presentation at the SUERF/JVI/OeNB Conference “Gender, money and finance – 1st Vienna Economic Dialogue”, May 20-21, 2021. The results presented are based on the paper “Do women matter on monetary policy boards?” joint with D. Masciandaro and D. Romelli, BAFFI CAREFIN Centre Research Paper No. 2020-148.

Catalyst, Quick Take: Women in Management (August 11, 2020).

IPU, UN-Women, Women in Politics Map, 2021.

Profeta, P. Gender equality and public policy. Measuring progress in Europe. Cambridge University Press.

Ferrari, G., Ferraro, V., Profeta, P. and Pronzato, C. (2021) Do board gender quotas matter? Selection, performance and stock market effects. Management Science, forthcoming.

Hessami, Z. and Lopes da Fonseca, M. (2020) Female political representation and substantive effects on policies: a literature review. European Journal of Political Economy, 63: 101896.

Masciandaro, D., Profeta, P. and Romelli, D. (2020) Do women matter in monetary policy boards? Baffi-Carefin working paper 148.

It is important to note that we are cautious in inferring causality between the gender composition of boards and monetary policy outcomes, since our analysis cannot provide a causal interpretation.