The European Green Deal was introduced by the European Commission in December 2019 as the new long-term strategy of the EU. The goal is to reduce net greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030 (compared to 1990 levels) and for Europe to become the first climate-neutral continent by 2050 (European Commission, 2021).1

The transition towards a net zero economy and energy independence by 2050 is estimated to require large annual multiannual investments worldwide by 2030 to around USD 4 trillion (IEA, 2021). Becoming the world’s first climate-neutral bloc by 2050 is a great challenge but also a great opportunity. The EU budget alone cannot be enough to tackle climate change or to meet the massive global investment needs (Dombrovskis, 2020). Member States and private actors will need to play an important role in financing the European Green Deal. The European economy relies heavily on bank financing (ECB, 2023a). Banks need to increase their green investments while at the same time disinvest in non-green assets. Significant Risk Transfer (SRT) securitizations can support banks to facilitate the green transition to meet agreed net zero carbon objectives. However, this market segment while working fine in the recent past would require some changes and receive increased support to provide the required scale. This note describes what SRT is, how the SRT market could be scaled up to aid in the green transition challenge and the role the EU could play by leveraging one of its key institutions, namely the EIF, part of the EIB group.

The Significant Risk Transfer (SRT) securitization framework gives banks the possibility to deleverage their balance sheets by transferring to an investor the credit risk of a tranche of a loan portfolio and, in that way, obtain regulatory capital relief. Banks have been using this market to reduce Risk Weighted Assets (RWAs) since the 1990s, so the SRT market is not new (Gonzalez and Triandafil, 2023).

The SRT market2 has developed considerably in Europe recently with close to EUR 200 billion of notional volume transacted in 2022. SRT was introduced in the EU regulatory framework in 2006 following the Basel 2 agreement.3 Banks use SRT securitizations to free up balance sheet capacity for new lending to the real economy and optimize capital deployment towards more profitable lending projects. Banks achieve capital optimization in general by using synthetic transactions,4 with more traditional cash transactions taking a secondary role.

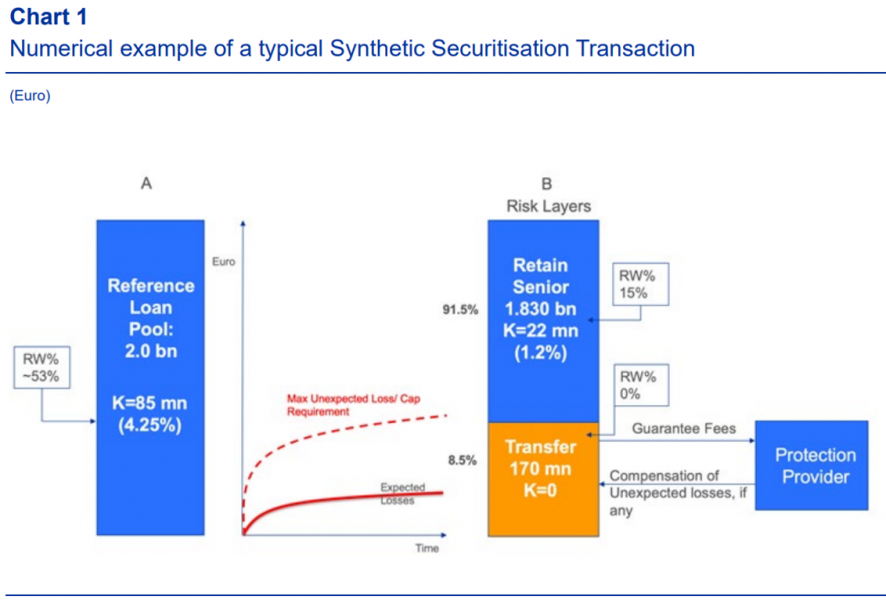

How could a bank use the capital relief obtained in an SRT transaction to move from holding brown assets in its balance sheet to more green assets? In the simplest 2-tranche securitization transaction depicted in Chart 1 below, an investor will provide direct risk protection and compensate the Bank in case losses occur in the first loss tranche, which typically covers the first and expected loss in the underlying reference (brown) portfolio. The first loss tranche is in this case transferred to the “Protection Seller” for a fee on the financial guarantee.5 Note that unlike in a traditional securitization, a Special Purpose Vehicle is not required in this type of structure, which increases simplicity and is cheaper in terms of legal documentation and can be used in jurisdictions lacking a securitization law (Gonzalez and Triandafil, 2023).

Chart 1 shows numerically the key benefits for the Bank in pursuing the synthetic SRT transaction. In this example, the underlying reference loan pool (of previously defined brown assets) is EUR 2.0 bn. The loan pool risk corresponds to a Risk Weight of around 53%, which would require the Bank with an 8% minimum capital to set aside EUR 85 million to meet its capital requirements.6 With the view to save on capital requirements and transition its balance sheet from brown to green assets, the Bank may decide to pursue SRT and obtain credit risk protection. The Investor and the Bank agree that 8.5% of the total portfolio will be allocated to the first loss tranche, and the remaining 91.5% to the Senior tranche. The CRR formulae allocate to the retained Senior tranche a much lower 15% Risk Weight or EUR 22 million of capital, whereas the first loss tranche will consume 0% RW as the risk is transferred7 and no longer sits on the Bank’s balance sheet. Overall, the transaction will provide the Bank with a substantial capital saving of around EUR 63 million in comparison to holding the portfolio on its balance sheet.8

Once the capital relief is achieved, the bank may deploy this capital in new green loan projects without the need to raise new expensive capital, ‘greening’ its balance sheet.

While the SRT market is now mature and the factors underpinning its growth and functioning are well understood by regulators and policy makers (EBA 2017 and 2020), we argue that more could be done to scale up its use to support the massive funding needs for the green transition. In particular, the market is still concentrated around a small number of banks and protection providers. To scale up and develop the market, several measures could be promoted.

The European Investment Fund, part of the European Investment Bank Group as the investment arm of the EU could support the risk transfer market for green transition with a new scheme that is standardized, simple, high quality and has the potential to attract new funds not currently deployed in the SRT market. The EIF role for green transition (EIBG, 2020) could resemble that of US agencies for US residential mortgage risk albeit with little risk to EU taxpayers.

The European Investment Fund has achieved a prime position in the European SRT market, notably for SME transactions (EIF, 2023). It has been an active participant in analyzing transactions, performing due diligence on the underlying loan portfolios, negotiating documentation and closely monitoring deal performance with an impressive track record over the years. Crucially, SRT transactions where the EIF participates as guarantor can benefit from its Multilateral Development Bank status to achieve capital relief at lower overall costs.

We argue that the participation of the EIF could scale up the SRT market to meet the European green transition challenge along the following lines:

The potential for broadening private sector participation of holders of long-term capital (e.g., re/insurers and institutional pension funds).

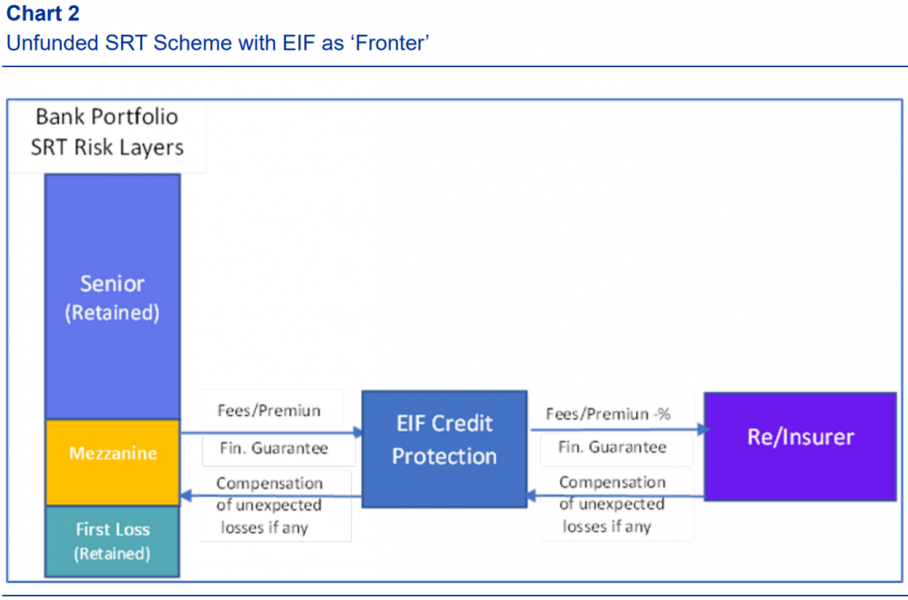

The EIF participation as a “fronter” in synthetic securitizations could bring more flexibility in areas that are constraining banks and private sector participation. A notable example is in the use in SRT transactions of unfunded protection from re/insurers. Unfunded protection is permitted under the synthetic securitisation framework but not (yet) under the EU Simple Transparent and Standardized (STS) securitisation regime. At a time when bank demand for SRT transactions is growing and interest rate increases are making traditional funded solution more expensive, banks who use unfunded protection lose the possibility of benefiting from using the STS regime seriously affecting their cost of released capital. This issue would be addressed if the EIF with its 0% risk weight were to “front” on behalf of the insurers, while insurers would not need to pre-fund their guarantees bringing down overall transactions’ costs. This would also allow regulators to gather further evidence of the robustness of unfunded protection before expanding STS eligibility to it.

The insurance sector is large and long capital. For example, European insurers and reinsurers have aggregate own funds of Euro 1 trillion according to EIOPA, which is over 2 times the solvency capital ratio required. While credit risk represents around 85% of European bank capital requirements according to the ECB (ECB, 2023b), it is much less relevant for re/insurers leaving room for growth. For example, the Credit and Surety segment represent only 2% of written premium for European insurers according to EIOPA.

Chart 2 shows one possible flow of guarantees and fees in such EIF scheme, with the EIF retaining a small portion of the fees paid by the protection buyer. This would help the EIF meet the costs and risks incurred in running the scheme. Note that the EIF would receive counter guarantees by private re/insurers without collateral, requiring an appropriate risk framework for counterparty risk. Funded protection providers may, too, act as reinsurers to the EIF.

Such a scheme would not be completely new in Europe or for that matter the EIF who is currently fronting on behalf of its parent EIB with a similar format to what is described in Chart 2. Likewise, the German development bank, Kredit fur Wiederaufbau used a comparable synthetic securitization scheme up until 2008. By providing 0% RWA guarantees to banks on selected portfolios, tranching the credit risk and allocating it to commercial third parties, KfW offered significant capital benefits to German mortgage lenders and corporate lenders on over euro 100bn of loans while incurring negligible credit losses (Krauss and Cerveny, 2015). Similarly, in the US, Government Sponsored Entities and in particular Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac have been at the core of the mortgage credit risk transfer markets for many decades.

The above structure is very flexible and can easily be adapted to incorporate other EU policies, such as social impact or competitiveness and growth objectives. This is better done at the level of specific underwriting criteria in dedicated programs, while the structural features (EIF guarantee with most of the risk transferred to market entities) would substantially remain the same.

We believe that there is an opportunity for Europe in the form of risk transfer securitizations to support the green transition. The EIF, as the best placed institution to implement such a scheme, could start with a small pilot program. The pilot should still have a measurable impact and an adequate diversity in geography and loan types, so probably an initial target of Euro 1bn of protected tranches covering the risk layer somewhat above expected lifetime losses and up to the senior floor attachment point according to regulatory capital models. Considering that EIF unfunded protection could provide STS eligibility such tranches would probably represent [5-7%] of overall exposure across most asset classes, so that Euro 1bn of protection would be applied to Euro 15-20bn of loans. Because the securitization approach is not 100% efficient, we can expect that the protection would thus enable about [70%] of such amount in new green lending, or Euro 10-15bn. By standardizing and simplifying risk transfer transaction structures and ensuring a strong quality and transparency as it is currently the case, the EIF could emerge as an important enabler in the necessary transition to a more sustainable and greener economy.

Dombrovskis, V. (2020) Remarks by Executive Vice-President Dombrovskis at the Conference on implementing the European Green Deal: Financing the Transition.

European Commission (2021), Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions ’Fit for 55’: delivering the EU’s 2030 Climate Target on the way to climate neutrality.

European Banking Authority (2017), Discussion paper on the Significant Risk Transfer in Securitisation.

European Banking Authority (2020), Report on significant risk transfer (SRT) in Securitisation transactions.

European Central Bank (2023a), 28th Survey on the access to finance by enterprises.

European Central Bank (2023b), Supervisory Banking Statistics for significant institutions Fourth quarter 2022.

European Investment Bank Group (2020) Climate Bank Roadmap 2021-2025.

European Investment Fund (2023) Leading provider of guarantees and credit enhancement to catalyze SME lending across the EU.

European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (2022) European Insurance Overview 2022.

Gonzalez, F. and Triandafil, C. (2023), The European Securitisation Significant Risk Transfer Market of SSM supervised banks. ECB Working Paper mimeo.

International Energy Agency (2021), Net Zero by 2050: a Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector.

Krauss, S. and Cerveny, F. (2015), Why synthetic securitizations are important for the European Capital Markets Union.

In 2021, the COVID pandemic pushed the EU leaders to agree on a plan to invest in and support growth, which resulted in the launch of the Next Generation EU recovery plan. At least 30% of the EU budget (including Next Generation EU) was earmarked for tackling climate change and supporting green projects. This direction was further supported after the EU decided to work towards energy independence because of the war in Ukraine.

The SRT market is also referred to as capital risk transfer, bank risk sharing transaction or ‘reg cap’ trades market. This paper will use the term SRT as it is the terminology used in the EU regulatory framework.

Capital Requirements Directive 48/2006 implementing Basel framework in the EU and it has developed into a fully-fledged regulatory framework under the EU Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR) (see See Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 June 2013 on prudential requirements for credit institutions and investment firms and amending Regulation (EU) No 648/2012. (2013)).

Synthetic SRT transactions, also called on-balance sheet securitizations, transfer tranches of credit risk to third parties while maintaining the protected exposures on the bank balance sheet. Traditional securitizations require the sale of assets to a Special Purpose Vehicle.

In a typical SRT transaction with 3 tranches, the first loss tranche is not typically transferred to an investor, but it is retained by the Bank.

This is EUR 2 bn x 53% x 8% = 84.8 million. This implies a Kirb of 53% x 8% = 4.25%. But banks would generally seek higher capital ratios than the minimum 8%. A bank with a CET1 ratio objective of 14% would put around EUR 150 million of capital aside for the underlying portfolio, which would make pursuing the SRT transaction much more compelling for the Bank.

Assuming the protection is fully collateralised or provided by an MDB. The benefit would be slightly lower if the guarantor was rated “A” or better and offered no collateral.

Banks will typically run a cost benefit analysis to critically judge whether the cost of equity generated by the potential SRT transaction falls below the internal hurdle rate (IRR). If the cost of equity due to SRT goes above the IRR, the transaction will not be executed. Cost of equity includes all fees paid by the bank to structure the transaction (advisory, legal, etc). Other elements considered by the bank are the funding cost and the tax benefit.